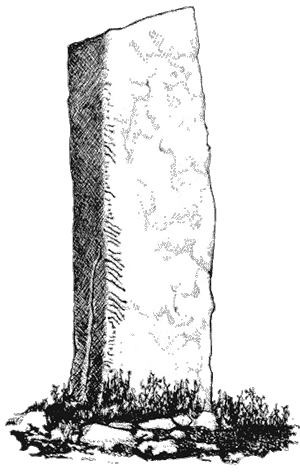

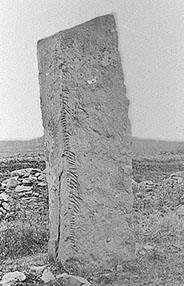

Breastagh Ogham Stone

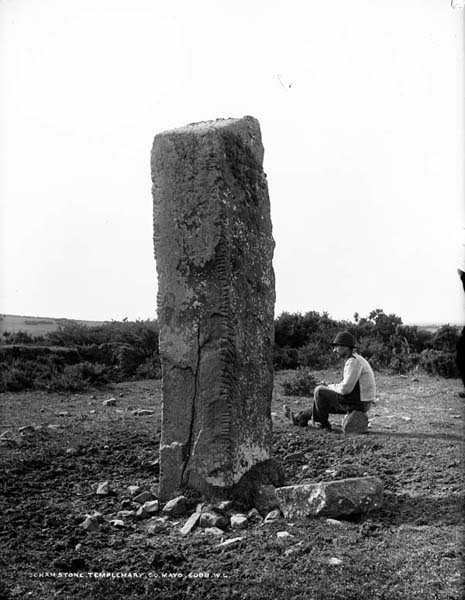

An outstanding example of a square sectioned standing stone, this former Ailandruadh or ‘Druids Stone or Pillar’ measures 3.5 metres in height and was probably erected in the Bronze Age with its inscription chiselled sometime about 300-600 AD. At one the inscription was the longest ogham legend in existence in Ireland.

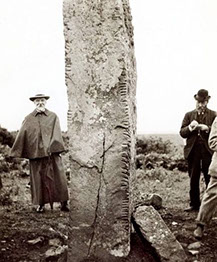

-crop-u2919.jpg) Re-erected by members of the Royal Irish Academy, under the direction of Sir Samuel Ferguson in 1853, having been almost buried for several generations, it is now known as ‘The Breastagh Ogham Stone’ from its location in the townland of Breastagh.

Re-erected by members of the Royal Irish Academy, under the direction of Sir Samuel Ferguson in 1853, having been almost buried for several generations, it is now known as ‘The Breastagh Ogham Stone’ from its location in the townland of Breastagh.

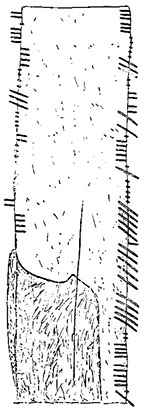

Carved vertically into ancient stones which pre-date the written language by centuries, Ogham (Ohm) which is called after Ogmios, the Celtic God of writing, is a script composed of straight lines placed at various angles and arranged in rows on different sides of a stem line. Ogham writing originally consisted of an alphabet of twenty, and later twenty-five letters.

Originating in Druidic days, Ogham, which also resembles the Germanic Runes, is read upwards from the lowest line. Later, with the coming of organised Christianity to Ireland in the fifth-century, the monks adapted Ogham stones to the Christian religion and several stones have been discovered throughout the country which have Christian markings carved on them in place of or imposed on the Ogham. It is thought that the Breastagh stone is unique, as it is possibly the only stone in existence bearing an Ogham inscription where the person or family mentioned, is known independently in history.

The Ogham markings are still clearly visible and while one side, regrettably almost worn, reads a fairly meaningless: ‘LGG....SD....LEESIA’ the other reads: ‘MAQCORBBRIMAQAMLOITT’ which is interpreted as ‘The Son of Corbbri, Son of Amloitt’. Tradition would have us believe that this particular stone commemorates the grandson of the illustrious and celebrated fifth-century King Amhalgaidh - pronounced ‘Awley,’ whose name is embedded in the local history, and after whom the Barony of Tirawly is named.

The Ogham markings are still clearly visible and while one side, regrettably almost worn, reads a fairly meaningless: ‘LGG....SD....LEESIA’ the other reads: ‘MAQCORBBRIMAQAMLOITT’ which is interpreted as ‘The Son of Corbbri, Son of Amloitt’. Tradition would have us believe that this particular stone commemorates the grandson of the illustrious and celebrated fifth-century King Amhalgaidh - pronounced ‘Awley,’ whose name is embedded in the local history, and after whom the Barony of Tirawly is named.

“On the way to Kilcummin - the site of the French landing in 1798 - you have immediately north of Palmerstown Bridge, on the roadside, the finest ‘Giants’ Graves’ I have ever seen; and hard by you have the old Dominican Monastery of Temple Mary-‘Rathfran of the Sweet Bells,’ as Mac Firbis calls it; and just at the mouth of the Palmerstown river you have, on the beach, two stones, pointing out where Tressi, wife of Awley, [Fearsad Tressi-Tressi’s Ferry/Ford] was drowned whilst bathing. A little farther, on the roadside, there is the finest pillar-stone, perhaps in Ireland, with Ogham inscriptions, indicating the burial-place ‘of the son of Carbry, the son of Awley.’ This stone was put standing [re-set in 1853] some thirty-five years ago, by the late Sir Samuel Ferguson. A little further on still you have the site of the ‘Wood of Fochuill,’ represented by the modern townland of Foghill, connected with the vision of St. Patrick—and all of these interesting objects and places are within a radius of a mile.”

(Journal, R.S.A.I., Vol. VIII., PT.III., 5th Sept 1888)

As far as we know, Stone Age Man, and the early civilisations which came in the aftermath of the Stone Age, did not have a written language. One way that these ancients differed from us moderns is that they did not communicate verbally to the same extent as we do today. They mostly lived in silence and as a result had a great and close connection to the natural forces around them. Talk was expressed mostly by the use of facial expressions and hands, similar to the global sign language of today which also uses arms, hands, fingers, in conjunction with lip reading. Often referred to as ‘a vocabulary of silence,’ Ogham was equivalent to that language, in use from the earliest times it was first inscribed sometime about 300 AD.

As far as we know, Stone Age Man, and the early civilisations which came in the aftermath of the Stone Age, did not have a written language. One way that these ancients differed from us moderns is that they did not communicate verbally to the same extent as we do today. They mostly lived in silence and as a result had a great and close connection to the natural forces around them. Talk was expressed mostly by the use of facial expressions and hands, similar to the global sign language of today which also uses arms, hands, fingers, in conjunction with lip reading. Often referred to as ‘a vocabulary of silence,’ Ogham was equivalent to that language, in use from the earliest times it was first inscribed sometime about 300 AD.

The early monks, many of whom were former “Adders” or Druids, often took vows of silence, and depending on their abbot, these vows could be for specific periods, or in many instances, for life. This imposed silence did not preclude communication, however, because the brothers had to communicate in some form as they went about their daily tasks, so instead of speaking, they utilised Ogham and talked with their hands in the ancient pre- Christian manner. As Ogham grew to become a language of five groups of five letters, the five fingers of the right and left hand were used, and moved, as necessary, up and down, just as it appears on the stones, but initially, on a central line, the central line in this case being the body.

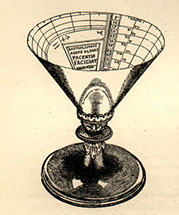

In 1980, an early chalice and paten were unearthed from a ninth-century monastic site at Derrynaflan in county Tipperary, the find which contained five liturgical vessels, the chalice, paten, paten stand, bronze basin and strainer, became known as ‘The Derrynaflan Hoard.’ After the Ardagh chalice, the Derrynaflan chalice is only the second ‘bell’ chalice found in Ireland while the paten is the first of its type recorded here. Dating to different periods, the artefacts did not constitute a full communion set.

It is believed that the chalice and paten, together with the strainer spoon were the astronomical and astrological instruments of the early monks. These enlightened individuals were the mathematicians, astrologers, astronomers, and alchemists of the known world, who had brought with them the ancient alchemical and magical practices of the Druids and incorporated them into the Christian religion. By placing the strainer in the chalice or on the surface of the paten and utilised in the form of a gnomon, the monks were able to calculate the path of the Sun, the Moon and the stars. This obscure practice of the ‘chalice dials’ was kept secret, because if it was known that these holy vessels were used in such a scientific fashion, the sacred transubstantiation of the mass would be viewed as being debased. The early bell-shaped chalices were used in the same manner as the later and more advanced, mostly German, chalice dials, which had a fixed central pin, or gnomon. The difference being that the strainer spoon was moved about the face of the dial with the boss (crystal) which was situated at the end of the handle representing the Moon or the Sun.

The paten was used in much the same fashion. Around the top rim there are twenty-four bosses which tell the hours from sunrise to sunset. The upper vertical rim of the paten has twelve bosses while the lower stand of the paten has eight bosses and many hold the belief that that the top half of the paten was originally turned on the stand to enable ‘differential dialling of the Sun’s magnetic fields and of the equinoxes, solstices and quarter days-the pattern of the Druidic year.’ The polished silver surface of the paten was also used as a sun-reflector for passing and transmitting Ogham messages over long distances from one settlement to another. This was a form of Morse code by light and messages were flashed either side of a central sight line between the two structures. This was the same principle as the coastal beacons lit in ancient times to warn of possible invasion, or from church spire to church spire, or round tower to round tower.

In the Ogham script there is a circle around the vertical line which signifies the phonetic of ‘oi.’ This ‘greeting’ is still used as a modern term of attracting someone’s attention by shouting ‘oi’ or as the town criers used to say ‘oyez’ which is the old French for ‘hear.’ Added to which, Christian priests still use vessels in their services without having any knowledge of their ancient alternative and scientific purposes.

In the Ogham script there is a circle around the vertical line which signifies the phonetic of ‘oi.’ This ‘greeting’ is still used as a modern term of attracting someone’s attention by shouting ‘oi’ or as the town criers used to say ‘oyez’ which is the old French for ‘hear.’ Added to which, Christian priests still use vessels in their services without having any knowledge of their ancient alternative and scientific purposes.

According to the nineteenth century author and antiquarian, John O Donovan, nearby Rathfran was one of the forts of the kings of the Hy Fiachrach of the Moy, descendants of Fiachra Ealgach. So therefore Breastagh is deemed by him to be an authentic place where a memorial to a man of rank, one descended from royalty and in this case Amhalgaidh, King of Connacht (not Amhalgaidh, son of Daithi, whose descendants settled in county Meath) might be found. He dates the carving to the first half of the sixth century.

Two other standing stones may also be viewed in the vicinity, a very fine tall/slim one measuring upwards of twelve feet in height at nearby Foghill, Leac Balbeni - ‘the Stone of Balbeni’ and another at Banagher-locals know this latter stone as the ‘Liagán’ which translates variously as ‘Obelisk, Pillar-Stone, Monolith, or Tomb-Stone.’

Legend would have us believe that this smaller stone, which stands about six feet in height, once marked the burial spot of the first locals to die from cholera. The story goes that a malevolent fog came in from the sea carrying with it the dreaded disease and in a short time an entire village was wiped out. It is also claimed in local tradition that the time-worn symmetric stones form a line that may once have been the fifth century boundary markers of the ancient territories of Caoile Conall –‘Conall’s Territory’ and the Lagan.

A little further to the south of the Breastagh Stone, in the townland of Carbad Mor, a ruined double-court tomb may be found. This ruin contains a cairn and the remains of two circular courts, each one leading into its own segmented gallery, while about eight hundred metres north, north-east of this structure, in Rathfranpark, the remains of a large wedge tomb may be viewed. This particular tomb is built of several large stones measuring almost five feet in height and close by are what remains of a stone circle. Another ruined wedge-tomb is located in Rathfran South, while one kilometre east north east of the Breastagh stone, close by a hill to the rear of Summerhill House are two stone circles about one hundred metres apart. The larger of the two has thirteen stones and is fifteen metres in diameter, while the smaller circle measures seven metres in diameter. Ask a local for directions as these circles are not signposted!

Another method of utilising Ogham was by the Tábhall-Lorg or ‘Tablet Staff’, also variously known as Taibhli-Filidh, Tamlorga-Filidh, Flesc-Filidh - ‘The Poet’s Staff or Tablet’. Fashioned from birch or beech, these relics of times past were collections of wooden sticks on which Ogham writing was carved. Held together by a thong of leather, the lengths of wood were carried by the ‘enlightened ones,’poets, druids, and teachers, and when opened out into a fan-shape, they could be read and interpreted.

Tábhall-Lorg“The ancient Gaedhelic Tablet took, I believe, more the form of a fan than a tablet, a fan which, when closed, took the shape of a staff, and which indeed actually served as such to the poet and historian.” (Eugene O’Curry)

Tábhall-Lorg“The ancient Gaedhelic Tablet took, I believe, more the form of a fan than a tablet, a fan which, when closed, took the shape of a staff, and which indeed actually served as such to the poet and historian.” (Eugene O’Curry)

It is frequently mentioned in our ancient manuscripts that genealogy, history, poetry, and other events were recorded by the Druids and teachers in this manner, and the laws formed in ancient Ireland known as Na Breithibh Nimhedh - ‘The Brehon Laws,’ decreed that only the aforementioned groups were allowed carry the ‘Tablet Staff.’ This particular method of recording features prominently in the epic Irish tale of enchantment and expedition, The Voyage of Bran, in which the legendary Bran wrote fifty quatrains in Ogham on his Tábhall-Lorg detailing his many centuries of wandering, before casting the staff on the waters, so that the waves might carry his story ashore.

Realms of Mystery

Local folklore or “ghostlore,” more like, would have us believe that the age-old area stretching from the magnificently masoned arched bridge of Palmerstown to Breastagh is the territory inhabited and haunted by the “Dullahan,” a well-known Irish “Fairy” of the ‘Solitary Class’: a tSióg Mhallaithe or ‘Wicked Fairy.’

A most gruesome thing, by all accounts, the “Dullahan,” who it is said, is an object of curiosity to the stranger and an object of dread to the timid and superstitious, holds high revel throughout this region when the shades of night have fallen, and is said by those who have seen him to have no head, or else he is seen carrying his head under his arm. Often he is spotted driving a black coach drawn by six headless horses. According to the lore, if by chance this vehicle of dread trundles to your door, and if you are foolish enough to open the door to its grim handler, beware, because a cup of blood will be flung in your face: unsurprisingly, such a visit is considered an omen of impending death!

The strong belief in an neighbourly other-world community, albeit one which shares the habitat with us, but one which is not necessarily visible to us, is found in many traditions, but it is probably strongest in the Irish tradition. Early Irish literature informs us how after death, the “dead” live on in such a world parallel to the living world, and these people can intermingle with human life when they so wish-but nearly always at special times of the year.

The literature further informs that these forebears were said to have their residences in the ancient burial mounds or tumuli scattered about the country. The ancient Irish word for a tumulus was sídh which in time was used to refer to the actual inhabitants of the tumuli. Consequentially, in Irish folklore there exists a ‘fairy-faith,’ wherein the inhabitants of the other-world were referred to as ‘the people of the sídh (modern sí).

However, due to a combination of fear and respect, the sí reference is seldom used and usually avoided: in other words, evasive expressions such as na daoine uaisle (the nobles) and na daoine maithe (the good people) are used instead. Moreover, in everyday speech, these titles are rarely if ever used and the inhabitants of the other-world are simply referred to as ‘they’ or ‘them,’ and while the term ‘the fairies’ is commonly used in English, it is avoided in Irish folk speech.

One of Ireland’s greatest ever folklorists, the inspired scholar Dáithí O Hogáin noted: “The general tendency is for superstition to situate these spiritual beings in features of the landscape which are cultural rather than natural. In the same way as the early Irish located the Celtic deities in the old burial sites...so the folk sensed that ancient constructions were the proper place for the fairies. Throughout Ireland, there are many earthenwork forts, or ‘raths’-actually the remains of early dwelling-sites. It was widely believed that these raths were inhabited by the fairies. Medieval Irish literature explains this belief by saying that a spiritual people known as Tuatha Dé Danann, were defeated in battle by our Irish ancestors, and accepted the terms of a treaty whereby they would live in underground dwellings. This, however, was learned invention. The earlier tradition must have been that both deities and the dead had their residences in sacred places. Something of this survives in the frequent folk statements that sites such as hilltop cairns are inhabited by the fairies.”

It is often cited in local lore that at certain times, and nearly always at night, music can sometimes be heard emanating from places reputed to be fairy-dwellings as the inhabitants engage in revelry within, and travellers who found themselves abroad at night were on many occasions exposed to hurling matches being played by these inhabitants in fields adjacent to such raths.

Furthermore, in another image of human customs, the fairy inhabitants were thought to farm mystical livestock, and many stories abound which tell of fairy men arriving at markets to buy and sell. The lore also relates that any unfortunate farmer who unwittingly sold his livestock to one of these “fairy farmers” and who in turn was in receipt of money, be it coins or notes, soon discovered to their dismay, that as soon as the buyer had departed the market, the money turned into dry withered leaves.

Now there are many extant tales of foolish unscrupulous individuals who knowingly and wilfully ignoring fairy edict, interfered with, or dug up, or even in some cases levelled one of these raths, and as a result met with some dreadful misfortune. Similarly, it is told that a solitary tree, particularly a whitethorn, was always known as a crann sí (fairy tree) and to be of special importance and significance to the fairies, and if one of these tress was interfered with in any way, the culprit was liable to meet with a terrible accident, or in some cases, even death.

The old traditions, both oral and written, tell of the fairies fighting great battles among themselves. So it is not surprising to discover that many of our ancestors believed that certain noises heard at night were often interpreted as being the sounds of “the good people” doing battle. The discovery of prehistoric arrowheads and other implements in or about the vicinity of these raths only proved to confirm the belief. In addition, slopped milk discovered on the ground in the morning was usually construed as fairy blood spilled during battle, as fairy blood was thought to be white in colour. It is also told that the fairies often kidnapped the best human hurlers for their teams and that they also carried off accomplished musicians to provide extra entertainment at their other world gatherings. Apparently, if a human being partook of any of the sumptuous fairy refreshments on offer at one of these events, it was believed that the fairies were very generous, he or she would never be able to return to this earthly world.

Moreover, many stories are also told of the fairies bestowing artistic gifts upon humans, especially in music and poetry, and many detail the lives of musicians and poets who acquired their talents having fallen asleep on a fairy rath. Several of these individuals were believed to have been blind, or at least reported to have had bad eyesight, and this social reality was explained by the claim that the artists had lost their sight after the bright glory of a fairy vision. In fact, the great blind Irish harper and composer, Turlough O Carolan, is reputed to have fallen asleep in a fairy rath one night and to have woken up with many additional musical attributes.

As touched on earlier, there once was a powerful belief in fairy abduction, and this belief was to the fore regarding children and mothers who had just given birth; this belief was dramatised hundreds of years ago by the introduction into our folklore of a European legend.

According to the tale, a particular family with a newborn baby had a friend who noticed, then commented on the fact that the appearance of the baby had changed-something the family were apparently unable to see. When this was investigated it transpired that the real baby had in fact been taken by the fairies and a changeling substituted in its place. As the custom demanded, the friend placed the tongs in the embers of the fire, and when the implelment was red-hot he threatened the changeling with it, who immediately leapt from the cradle and darted out the door into a nearby fairy rath. In a short time, the real baby was mysteriously returned unharmed.

The distinctive feature of outwitting humans by means of a trick occurs frequently in Irish legend and many of these tales concern the leprechaun, this little but extremely well “turned out” fellow, who often claims to be a shoemaker to the fairies.

According to the tradition of the North West, the local leprechauns have been described as wearing a red coat with seven buttons in each row, along with a cocked-hat, on the point of which he often spins like a spinning-top. He is also reputed to have a hidden crock of gold, the whereabouts of which he is honour bound to disclose if by chance he is caught and kept within sight. Nearly always alone when encountered, this elusive fellow may have originated in early European folk literature detailing treasure-guarding dwarves. His original name in Irish was luchorpán, a ‘small bodied fellow,’ and throughout Ireland he is known by local variants such as luchramán, luchragán, clúracán, loimreachán, as well as leipreachán.

The most famous of all other-world beings in Ireland, and another fairy of the tSióg Mhallaithe or ‘Wicked Fairy’ class is the Banshee from the Irish Bean Sí- ‘Other-World Woman’ or ‘Fairy Woman.’ A distinctive Gaelic personage who may have evolved from ancient beliefs of the land-goddess as patroness of chieftains and kings, the folk belief in the Banshee is very strong, even today, and it is claimed her wailing cry is still heard near the home of someone who is about to die.

Irish tradition informs us that on the eve of the famous Battle of Clontarf in 1014, King Brian Boru was visited by his clan Banshee, ‘Evan of Craiglee,’ who foretold the monarch’s death on the following day. It would also appear that the Banshee is aware of the fortunes and plight of the Irish all over the world as many claim to have heard her wailing lamentation only to learn shortly afterwards that a relative had died abroad. Now some old people maintain, wrongly, in the opinion of some, that she never goes beyond the seas, but always dwells in her own place; contrary to this, it is recorded that sightings and wailings of the Banshee have been documented in England and as far as certain South American countries.

In some parts of the country, the Banshee, if sighted, is a sure sign of impending death. From sightings she is variously referenced as being an old woman, normally seen sitting, but crying forlornly, while combing or brushing her hair and gazing into a mirror-usually by a riverbank. Consequently, in days gone by if someone came upon a lost comb or hairbrush, he or she would not dare to touch it, especially if the article had no teeth or bristles, for the people feared that such items belonged to the Banshee and if touched or handled, the person directly involved or a member of their immediate family would die. The Banshee was usaully heard three nights before a death.

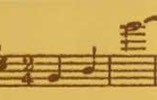

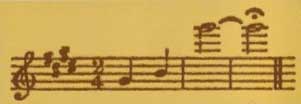

The above piece of music is the recorded cry/wail of a Banshee as heard and notated by a nineteenth century musician.