Kilcummin (Cill Chuimín - Cuimíns Church)

_4-crop-u6695.jpg)

Located a few short miles north of Breastagh is the historic and picturesque fishing village of Kilcummin; named for the church of Cuimín, a local folk- saint, it is now anglicised as ‘Cummin.’

Although there were reputed to have been numerous St Cuimíns,’ the Book of Lecan informs us that the one we are concerned with was known as Cuimín Fada-‘Tall or Long Cummin.’ A holy man, wise judge, and fair arbitrator in disputes, it is claimed that Cummin, who may have spent some time on Iona and who flourished in the seventh century, was a descendant of Conaing son of Fergus, making him a relative of the illustrious fifth- century King ‘Awley’- Amhalghaidh Mac Fiachrach.

It is traditionally told that as an infant, Cummín was discovered “shipwrecked” in a small boat which had been blown ashore close by present day Kilcummin at Poll a’ Doba-‘The Hole of the Dobe.’ The tradition further tells that the saintly infant was discovered by a cow whose incessant and boisterous licking of the boat alerted a local man named Machan (now Maughan), to the child’s presence. This individual was married to a woman named Loughney and the couple duly rescued and subsequently reared the little fellow and ever since stories abound concerning both his power and piety.

One such tale tells that when Cummin was still a boy, his foster father sent him to a field close by their home which he had just finished sowing with corn. The boy was instructed to frighten off the birds thereby preventing them from eating the newly-sown seed, a sort of ancient ‘living scarecrow,’ as it were. But much to the astonishment and it is said ‘consternation’ of his foster father, a short time afterwards the boy arrived home and just as he was about to be reprimanded for apparently not fulfilling his family duties, the youngster pointed to the small time-worn, wood and adobe church which stood close by. And there, confined within the walls of the church were all the birds of the area and because of this the corn field was safe from their attention.

It would be foolish to dismiss myths and legends as nothing more than a constituent of popular fantasy. The folk memory of Ireland is still very strong and while most legends may be exaggerated, they contain a kernel of truth. This particular legend is beautifully depicted in a stain glass window which may be viewed over the main entrance to St. Patrick’s Catholic Church at nearby Lacken.

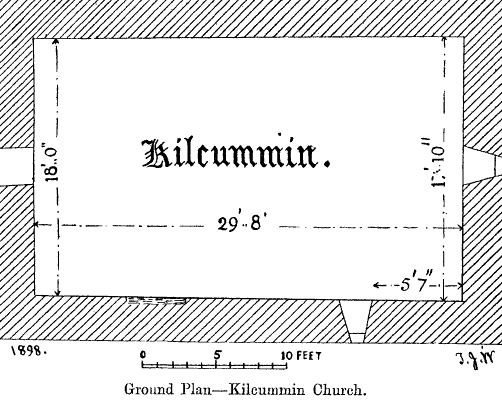

The remains of an early stone church attributed to Cummin and tentatively dated by the Ordnance Survey Letters “to a period not so late, even as the eight century” and constructed on the site of earlier church buildings survive here. In 1898, The Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland described this “remarkable” ancient building as “an oblong oratory” measuring it at 29’ 82’’ x 18’ with walls about 3’ thick. It is spoken of as being ‘a well preserved example of the first adoption of the true arch’ as seen in the radiating round arch of the door and windows.’

The remains of an early stone church attributed to Cummin and tentatively dated by the Ordnance Survey Letters “to a period not so late, even as the eight century” and constructed on the site of earlier church buildings survive here. In 1898, The Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland described this “remarkable” ancient building as “an oblong oratory” measuring it at 29’ 82’’ x 18’ with walls about 3’ thick. It is spoken of as being ‘a well preserved example of the first adoption of the true arch’ as seen in the radiating round arch of the door and windows.’

_4-crop-u6723.jpg)

North of the church is a cholera burial ground and a little further on, two standing stones may be found. It is believed that this is the location of the grave of St. Cummin, and many knowledgeable locals state that he lies buried “Idir an dá Leac”-‘between the two Standing Stones.’ A form of “headstone” incised with a cross having knobbed ends, round which are three circular ‘Patrick’s Crosses’ may be viewed between the two stones.

North of the church is a cholera burial ground and a little further on, two standing stones may be found. It is believed that this is the location of the grave of St. Cummin, and many knowledgeable locals state that he lies buried “Idir an dá Leac”-‘between the two Standing Stones.’ A form of “headstone” incised with a cross having knobbed ends, round which are three circular ‘Patrick’s Crosses’ may be viewed between the two stones.

On 21 June, 1803, the Rev. James Little of Lacken had an article published in The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy referencing an ‘ancient sepulchral stone or monument’ which he discovered close by the church in Kilcummin the previous year.

The markings were deciphered by Little and explained in the following way: “Died R.T. (suppose Ricard or Roderic Toole or Teigue &c.) prince (or precentor) of Killala, on May the 1st in the year of the Cross 1102.

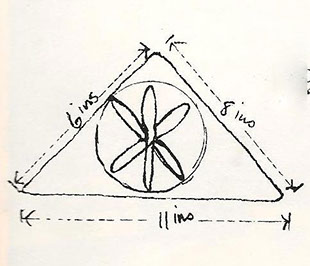

At one time another small stone with strange markings, albeit triangular in shape, was also to be seen on the grave. This particular stone was described in the Ordnance Survey Letters by Professor John O’Donovan as being a “stone with crosses at St. Cummins grave.” It is recounted locally that this unusual stone “vanished” during the latter part of the 1960s.

At one time another small stone with strange markings, albeit triangular in shape, was also to be seen on the grave. This particular stone was described in the Ordnance Survey Letters by Professor John O’Donovan as being a “stone with crosses at St. Cummins grave.” It is recounted locally that this unusual stone “vanished” during the latter part of the 1960s.

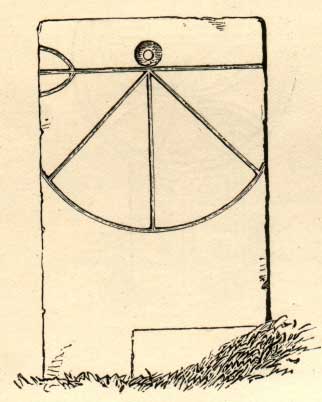

_8183x122.jpg) To the west of Cummin’s grave another extraordinary stone may be found. This stone which may date from about the sixth century has been variously described as a “Sun Dial” and “A Ship’s Sextant.” It is obvious from the present positioning of this particular stone that it is not in its original location.

To the west of Cummin’s grave another extraordinary stone may be found. This stone which may date from about the sixth century has been variously described as a “Sun Dial” and “A Ship’s Sextant.” It is obvious from the present positioning of this particular stone that it is not in its original location.

Kilcummin sundial

The Kilcummin sundial shows the horizontal line branched at the end, and the others lines dividing the day into three parts. It is known that in many areas, following the disappearance of the original gnomons that these stones were used as a ‘betrothal hole.’ In former times, especially during the ‘Penal Times’ when Catholicism was suppressed and priests outlawed and scarce on the ground, it was common among the Irish for a bride and groom to put a finger in the hole and pledge themselves in the presence of witnesses. This ‘engagement’ held good until a priest was procured to solemnize the marriage.

The Kilcummin sundial shows the horizontal line branched at the end, and the others lines dividing the day into three parts. It is known that in many areas, following the disappearance of the original gnomons that these stones were used as a ‘betrothal hole.’ In former times, especially during the ‘Penal Times’ when Catholicism was suppressed and priests outlawed and scarce on the ground, it was common among the Irish for a bride and groom to put a finger in the hole and pledge themselves in the presence of witnesses. This ‘engagement’ held good until a priest was procured to solemnize the marriage.

The first notion of dissecting time would, of course, be suggested by a tree, or a pole stuck in the soil, the shadow of which, moving from west to east, as the sun rose or declined in the sky, would lead ancient man to indicate by strokes on the ground the gradual progression of the hours during which the daylight lasted.

Further observation would discover that if the pole were slanted so as to point to the north star, and lie parallel with the earth’s axis, a sun-dial would be constructed that would measure the day. But the fixing of a complete instrument, varying in its lines and numbers, according to the locality, whether horizontally or vertically placed, would be a matter of progressive astronomical and mathematical calculation, which only the scientific could accomplish, long after the rude art of uncivilized man had discovered the means of ascertaining midday, and dividing into spaces the morning and afternoon.

Further observation would discover that if the pole were slanted so as to point to the north star, and lie parallel with the earth’s axis, a sun-dial would be constructed that would measure the day. But the fixing of a complete instrument, varying in its lines and numbers, according to the locality, whether horizontally or vertically placed, would be a matter of progressive astronomical and mathematical calculation, which only the scientific could accomplish, long after the rude art of uncivilized man had discovered the means of ascertaining midday, and dividing into spaces the morning and afternoon.

Herodotus (443 B.C.) says, “It was from the Babylonians that the Greeks learned concerning the pole, the gnomon, and the twelve parts of the day.” These twelve parts, however, would always differ in length according to the season, except at the equinox, because the ancients always reckoned their day from sunrise to sunset. The word “hour,” therefore, as they used it, must be regarded as an uncertain space of time, until it was accurately defined by astronomical investigation.

The earliest Jewish Scriptures give us no clear information as to how time was reckoned in the ancient world. “The evening and the morning were the first day” (Gen. i. 5) is the earliest description of a period of time whose duration we cannot precisely estimate. A week is also thus defined: “On the seventh day God ended His work which He had made, and He rested on the seventh day from all His work which He had made” (Gen. ii. 2).

“The Greeks of later times had a double mode of reckoning the hours. According to the popular method, they divided the period from sunrise to sunset into twelve equal parts. The hours reckoned upon this principle varied in length with the season. According to the more scientific method, the day and night at the equinox were severally divided into twelve equal parts, and each of them was reckoned as an hour. The division of the day into twelve parts, which Herodotus describes... was doubtless reckoned according to the former method. Πόλος signified a hollow hemisphere; and hence came to signify the basin or bowl of a sun-dial in which the hour lines were marked. In this sense it is used by Herodotus.” (Adapted from Sir G. C. Lewis, Astronomy of the Ancients.)

_2430x288.jpg) Further on in the Jewish history we find the day divided into four parts. In Nehemiah, ix. 3, we read: “They stood up in their place, and read in the book of the law of the Lord their God one fourth part of the day; and another fourth part they confessed, and worshipped the Lord their God.” This mode of computation appears to have lasted until the time of Christ; the householder in a parable by Mathew, when hiring servants, is described as going out at the third, sixth, and ninth hours to engage additional labourers, and afterwards at the eleventh hour before the day closed. The night was not divided into hours, but into military watches; the Jewish people recognised three such divisions, the “beginning of the watches” the “middle watch,” and the “morning watch” (later known as “the first watch,” “the second watch,” or the “third watch”). The Greeks and Romans had four of these night watches, and after the establishment of the Roman supremacy in Judæa it is evident that the division of the Jewish night was altered. Four relays of soldiers are spoken of as is the “fourth watch,” whilst the four watches are described as “even, midnight, cockcrowing, and morning.”

Further on in the Jewish history we find the day divided into four parts. In Nehemiah, ix. 3, we read: “They stood up in their place, and read in the book of the law of the Lord their God one fourth part of the day; and another fourth part they confessed, and worshipped the Lord their God.” This mode of computation appears to have lasted until the time of Christ; the householder in a parable by Mathew, when hiring servants, is described as going out at the third, sixth, and ninth hours to engage additional labourers, and afterwards at the eleventh hour before the day closed. The night was not divided into hours, but into military watches; the Jewish people recognised three such divisions, the “beginning of the watches” the “middle watch,” and the “morning watch” (later known as “the first watch,” “the second watch,” or the “third watch”). The Greeks and Romans had four of these night watches, and after the establishment of the Roman supremacy in Judæa it is evident that the division of the Jewish night was altered. Four relays of soldiers are spoken of as is the “fourth watch,” whilst the four watches are described as “even, midnight, cockcrowing, and morning.”

The mention of the hour as a distinct space of time occurs first in the Book of Daniel it is probable, therefore, that the Babylonian division of day and night into twelve parts was adopted by the Jews, and amalgamated with their own system. This was also the case with the Assyrians, amongst whom the calendar of their Accadian neighbours was in use as early as the reign of Tiglath Pileser I. “Along with the establishment of a settled calendar,” writes Professor Archibald Henry Sayce (1846-1933), “came the settled division of day and night. The old rough division of the night into three watches, which we find in the Old Testament, remained long in use; but although the astrological works of Sargon’s library do not know of any other reckoning of time, it was gradually superseded by a more accurate system.”

The Egyptians divided their day and night into twenty-four parts at a very early period.

Several historians make mention of ‘Leac Chuimín/ Cuimín-‘St. Cummin’s Stone,’ possibly an altar stone, which was at one time also present on Cummin’s grave and thought to have been used for cursing and other superstitious purposes.

Credited by the people as having ‘great powers,’ this particular ‘Cursing Stone’ was used mainly for the purpose of invoking misfortune on wrongdoers, especially such as were guilty of grave slander and it was to the aforementioned Maughan and Loughney families that the privilege of manipulating the stone belonged. Apparently the ceremony used in summoning the curse consisted of the stone being turned in a known pattern. It is told that the stone measured two feet by eighteen inches.

“…stones, of various sizes, arranged in such order that they cannot be easily reckoned; and, if you believe the natives, they cannot be reckoned at all. These stones are turned, and, if I understand them rightly, their order changed by the inhabitants on certain occasions, when they visit the shrine to wish good or evil against their neighbours. An aeir, or long-curse, has been often thus hurled against a private enemy.

(John O’ Donovan)

According to local historian Sean Lavin:-“If anybody for miles around felt badly wronged by someone and wished to use the cursing stone, the wronged person would first fast for fifteen days. Then this person would employ the Maughan or Loughney in charge of the Leac. One of these two families turned the maledictive stone. Results followed later which was usually the death of the offender. The sea would be in a “storm” for days. A Maughan man once turned it against a man called Waldron who because of this got mad a short while later.”

It was debated for many years whether as a result of this action the stone was smashed by a son of the Rev. James Little of Lacken, (remembered for his diary of the events of 1798), and a friend of the unfortunate Waldron, then further debated whether the fragments were collected and returned to the grave. In any case, the fragmented pieces were thought to have been subsequently removed in the early part of the nineteenth century by Dean Lyons p.p., Kilmore-Erris for “certain weighty reasons” and built into the altar of the newly constructed Cathedral at Ballina.

When referring to the stone in his Ecclesiastical History of Ireland, published in New York, in 1854, Father Thomas Walshe, formerly of Killala wrote: “It was removed by John Lyons, Dean of Killala and Pastor of Kilmore-Erris, to the church of Ballina, and when the present Cathedral was commenced, the broken slab was deposited in the work under the altar.”

This reference would definitely date the stone’s removal to a time after 1824 and its placing in the altar foundations previous to 1834. Construction of the Cathedral was begun in the early spring of 1827, but the altar was a later addition. In 1970 when the altar foundations were being excavated a search was made for the “Leac” by two esteemed local historians, but no trace was found.

There is a common extant tradition which maintains that at the time of its removal ‘a fragment or maybe more’ was surreptitiously retained and later buried by two local men ‘in the dead of night’ on land surrounding the well. It is also claimed that the two men were oath-bound never to reveal its exact whereabouts. Many believe that the elusive “relic” is indeed the altar stone of the Saint and that it never left the locality!

There is a belief that these ancient sundials were also used on occasion as cursing stones!

The small area between Cummin’s Grave and the two raised masonry tombs, both of which bear the coat of arms of the Bourke family (just inside the entrance gate) is where, for centuries, the ‘blessed clay’ has been accessed and removed. The tradition, one which is found throughout Ireland, maintains that the clay has ‘marvellous powers’ notably in fire prevention and the safety of travellers. In fact, there is a strong local folk belief that the possessor of this clay would never drown or meet with an accident, hence the fact that even today, many local families keep some in their homes, boats and cars, and down through the years many an emigrant has departed this area for distant lands armed with a handful of the ‘blessed clay.’ It is also claimed the when St. Patrick’s Church at Lacken was being built some of the aforementioned clay was placed in the foundation.

Situated a few yards north of the old church and graveyard “St. Cummin’s Blessed/Holy Well” may be found. Local tradition would have us believe that the present site of the well is not its original location, which may have been west of Cummin’s church. The story goes that sometime towards the end of the eighteenth century or the beginning of the nineteenth century, both the well and waters were desecrated by some malevolent individual and as a result the present well was “adopted.” One source claims that this may have happened in the aftermath of the 1798 Rebellion.

_14337x225.jpg) The last Sunday in July is given over to the veneration of St. Cummin when an annual Patron/Pattern is made at the well. This day of commemoration which is now known locally as “Garland Sunday,” was once known as ‘Domnach Crom Dubh’-‘Crom Dubh’s Sunday,’ or ‘The Sunday of the Black Stooped One.’ Crom Dubh was a feared time-worn Pagan Deity synonymous with the mythological deviant ‘Balor of the Evil Eye,’ whose glance, it is said ‘withered all, crops, animals, and humans alike.’ The waters from St. Cummins Well are reputed to have curative powers.

The last Sunday in July is given over to the veneration of St. Cummin when an annual Patron/Pattern is made at the well. This day of commemoration which is now known locally as “Garland Sunday,” was once known as ‘Domnach Crom Dubh’-‘Crom Dubh’s Sunday,’ or ‘The Sunday of the Black Stooped One.’ Crom Dubh was a feared time-worn Pagan Deity synonymous with the mythological deviant ‘Balor of the Evil Eye,’ whose glance, it is said ‘withered all, crops, animals, and humans alike.’ The waters from St. Cummins Well are reputed to have curative powers.

_10233x348.jpg) “At Kilcummin, in North Mayo, where tradition still cherishes the well used by St. Patrick for baptising his converts in the district, not a year has passed since then without the people holding a station at the well on the anniversary of that day and that day is the last Sunday of the seventh month. And in that place the Irish speakers call the month ‘Lughnas’ and the Sunday ‘Domhnach Chruim Duibh’ and the English speakers call the Sunday ‘Garland Sunday.’ And not a year from then till now but there has been a pattern at Kilcummin, where the well is ‘Tobar Chuimin,’ they call it.”

“At Kilcummin, in North Mayo, where tradition still cherishes the well used by St. Patrick for baptising his converts in the district, not a year has passed since then without the people holding a station at the well on the anniversary of that day and that day is the last Sunday of the seventh month. And in that place the Irish speakers call the month ‘Lughnas’ and the Sunday ‘Domhnach Chruim Duibh’ and the English speakers call the Sunday ‘Garland Sunday.’ And not a year from then till now but there has been a pattern at Kilcummin, where the well is ‘Tobar Chuimin,’ they call it.”

(Lub na Caillighe, ed. Joseph Lloyd, Gill and Son. 1910)

Bessie’s Bar is named for Bessie Munnelly, a local lady and renowned “melodeon” player who once owned and ran the bar-she lived next door. It is claimed in the locality that a “bar of sorts,” an unlicensed ‘Shebeen,’ was opened here sometime after the Great Famine of 1847 and this information is corroborated by the fact that the Ordnance Survey Maps of 1838 make no mention of a structure on this spot.

Bessie’s Bar is named for Bessie Munnelly, a local lady and renowned “melodeon” player who once owned and ran the bar-she lived next door. It is claimed in the locality that a “bar of sorts,” an unlicensed ‘Shebeen,’ was opened here sometime after the Great Famine of 1847 and this information is corroborated by the fact that the Ordnance Survey Maps of 1838 make no mention of a structure on this spot.

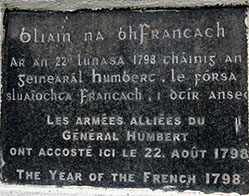

Kilcummin is particularly famous in Irish history as the place, where, according to the song The Men of the West, ‘on the eve of a bright harvest day,’ 22 August, 1798, French General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert came ashore with his small expeditionary force of 1,019 troops, thus initiating the military campaign which became known colloquially as ‘the Hurry’ and caused 1798 to be remembered as Bliain na bhFrancach-‘The Year of the French.’

Kilcummin is particularly famous in Irish history as the place, where, according to the song The Men of the West, ‘on the eve of a bright harvest day,’ 22 August, 1798, French General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert came ashore with his small expeditionary force of 1,019 troops, thus initiating the military campaign which became known colloquially as ‘the Hurry’ and caused 1798 to be remembered as Bliain na bhFrancach-‘The Year of the French.’

The very spot where Humbert disembarked is known as Leac A’ Chaonaigh-‘The Flagstone of the Green Moss.’ Situated just north of the headland, it may still be accessed with “spectacular” ease. The actual stone on which Humbert first set foot is still in the locality, having been removed from the shore by Peter Nealon in the latter part of the nineteenth century. According to local tradition ‘Humbert’s Stone’ as it is known, was to have been used as the plinth for the statue of Charles Stewart Parnell, which was being erected in Dublin at the time.

The very spot where Humbert disembarked is known as Leac A’ Chaonaigh-‘The Flagstone of the Green Moss.’ Situated just north of the headland, it may still be accessed with “spectacular” ease. The actual stone on which Humbert first set foot is still in the locality, having been removed from the shore by Peter Nealon in the latter part of the nineteenth century. According to local tradition ‘Humbert’s Stone’ as it is known, was to have been used as the plinth for the statue of Charles Stewart Parnell, which was being erected in Dublin at the time.

The Year of the French-1798

The Year of the French-1798

Chronology of an Expedition: General Humbert’s Army of Ireland, 1798.

July 19: The French Directory sanctions the sending of three military expeditions to Ireland and gives command of the first to General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert.

August 6: General Humbert’s Army of Ireland sets sail from La Rochelle on board three frigates, The Concorde, the Médée, and the Franchise, under the naval command of Daniel Savary.

August 22: The French vessels arrive in Killala Bay, land at Kilcummin and capture the town of Killala in a two-pronged attack. The local United Irish leader Captain Niall Kerrigan leads one attack from the area called ‘The Acres,’ the other from Mullaghorn, through George’s Street, is led by the French officer Sarrazin. Irish recruits flock to join them.

August 23-24: The new Franco-Irish army captures Ballina after defeating a British force at nearby Moyne. The three French frigates sail for France. They return two months later with another army of similar size under Adjutant General Cortez who realises that he has arrived too late and turns back.

August 23-24: The new Franco-Irish army captures Ballina after defeating a British force at nearby Moyne. The three French frigates sail for France. They return two months later with another army of similar size under Adjutant General Cortez who realises that he has arrived too late and turns back.

August 26-27: General Humbert departs Killala leaving 200 men behind to defend the town and proceeds to Ballina. From Ballina his army of 1,500 French and Irish avoid Foxford and take an alternative route to Castlebar via the village of Lahardane, across the mountains to the west of Lough Conn and through “The Windy Gap”-Barnageeha.

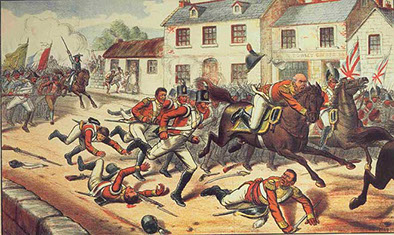

August 27: “The Races of Castlebar”: Defeating a much larger force commanded by General Lake, Humbert takes Castlebar and the majority of the British troops flee first to Hollymount in county Mayo, then Tuam in county Galway: some gallop with breakneck speed as far as Athlone, county Westmeath. In their haste they leave behind twelve pieces of artillery and substantial supplies of ammunition and stores. The speed with which the British fled the field gave rise to the vernacular title “The Races of Castlebar.”

August 27: “The Races of Castlebar”: Defeating a much larger force commanded by General Lake, Humbert takes Castlebar and the majority of the British troops flee first to Hollymount in county Mayo, then Tuam in county Galway: some gallop with breakneck speed as far as Athlone, county Westmeath. In their haste they leave behind twelve pieces of artillery and substantial supplies of ammunition and stores. The speed with which the British fled the field gave rise to the vernacular title “The Races of Castlebar.”

August 28: The British garrison withdraws from Foxford to Boyle, county Roscommon. Franco-Irish troops seize the strategic Mayo towns of Westport, Newport, Swinford, Ballinrobe and Hollymount: Claremorris is already in rebel hands. Cornwallis arrives in Athlone at the head of a considerable force but resolves not to counterattack until he has assembled and positioned his entire army.

August 31: In Castlebar, Humbert proclaims the Republic of Connaught and installs John Moore as its first President; he also sets up a civil administration in the town and begins training hundreds more rebel recruits.

August 31: In Castlebar, Humbert proclaims the Republic of Connaught and installs John Moore as its first President; he also sets up a civil administration in the town and begins training hundreds more rebel recruits.

September 3-4: Cornwallis retakes Hollymount and begins preparations for a dawn attack on Castlebar. Leaving behind a small garrison, Humbert withdraws and advances through Bohola and Swinford towards county Sligo, covering a distance of ninety-three kilometres in thirty-six hours. He orders the majority of the French garrison in Killala to link up with him at Tubbercurry, county Sligo where they repulse a British attack.

September 5: At Collooney, county Sligo, the Franco-Irish army defeat a sizeable British force under the command of Colonel Vereker. Cornwallis divides his army in two: one half commanded by General Lake is despatched to pursue Humbert from the rear, while the other, under his command, hold the line of the River Shannon. United Irishmen in Longford and Westmeath rise. They fail to seize the town of Granard but succeed in capturing Wilson’s Hospital, near Mullingar. Humbert who is at Manorhamilton, county Leitrim, resolves to link up with these insurgents and strike for Dublin. He therefore changes direction, abandoning some pieces of artillery to make more speed.

September 6: The decreasing Franco-Irish army reach Drumkeerin in Leitrim. Humbert rejects terms for surrender offered by and envoy from Lord Cornwallis.

September 7: Shortly before noon Humbert’s army succeeds in crossing the Shannon at Ballintra Bridge, south of Lough Allen. While attempting to blow the bridge they are engaged by the British and succeed in repulsing the attack-they fail to demolish the bridge. They rest the night at Cloone south Leitrim. Cornwallis with an army of 15,000 is just five miles away at Mohill while General Lake with a similar sized force is close on his heels. Early the next morning the Franco-Irish depart Cloone but their advance is checked close by the village of Ballinamuck, in county Longford.

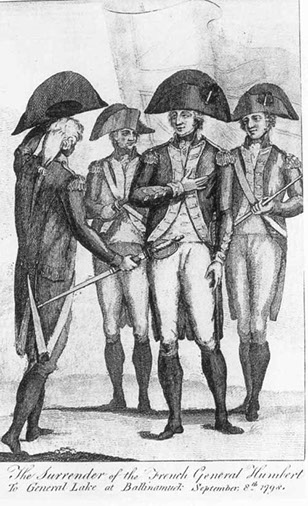

September 8: The Battle of Ballinamuck: General Lake launches an attack from the rear and the French second-in-command, General Sarrazin, surrenders the rear guard. Hostilities continue for an hour before Humbert who is greatly outnumbered surrenders. The French are treated as prisoners of war and transported, first to Dublin, then to England, before being repatriated in prisoner exchanges. Their Irish allies are shown no mercy and upwards of six hundred are massacred on the spot. Some escape, but hundreds more Irish prisoners are hanged at Longford and Carrick-on-Shannon.

September 8: The Battle of Ballinamuck: General Lake launches an attack from the rear and the French second-in-command, General Sarrazin, surrenders the rear guard. Hostilities continue for an hour before Humbert who is greatly outnumbered surrenders. The French are treated as prisoners of war and transported, first to Dublin, then to England, before being repatriated in prisoner exchanges. Their Irish allies are shown no mercy and upwards of six hundred are massacred on the spot. Some escape, but hundreds more Irish prisoners are hanged at Longford and Carrick-on-Shannon.

September 21-23: British General Trench commanding a large force leads a three-pronged attack on Killala which is still garrisoned by a small Franco-Irish force. He takes the town but over 600 people, mostly civilians, are butchered, many on the approach to Killala from Ballina. Afterwards this stretch of roadway was known as ‘The Pathway of the Slaughter.’

“Had Humbert’s expedition not taken place at a period when the attention of Europe was riveted by Bonaparte and his schemes of Oriental conquest, the episode would doubtless have figured in history side by side with the Bridge of Aricola, the Passage of the St. Bernhard, the Charge of the Light Brigade, and other traditions.”

(Valerian Gribayédoff)

For more information on "The Year of the French", please visit facebook.com/inhumbertsfootsteps

The Cursing Stone of Kilcummin

(IFC National Folklore Collection from Banagher National School, Roll No. 13808: collected by Teresa Kelly from John Kelly, aged 81 years, Church Village)

There is a stone in the grave-yard in Kilcummin and it is said that anyone wh wanted revenge on their neighbour would turn the stone in the night and a great storm would rise and carry the person away. People from all parts of the world used to come and they used to turn the stone.

There was a one woman and she had badness in her for her neighbour. She turned the stone in the night and immediately a great storm arose and the man was carried off.

The priests that was in Ballina heard it and they came down. There was an old man in the village named Martin Hughes and they brought him down to the grave-yard. There was a good deal of children outside the grave-yard. The priests told the old man to put the children away.

They got spades and shovels and they dug a hole down in the ground and put one half of the stone in the ground and the priests brought the other half with them and put it under the altar in Ballina.

St. Patrick And Crom Dubh

(Collected and translated from the Irish by Douglas Hyde)

This legend, told by Michael Mac Ruaidhri of Ballycastle, Co. Mayo, is evidently a confused reminiscence of Crom Cruach, the great pagan idol which was overthrown by St. Patrick. Though Crom appears as a man in this story, yet the remark that the people thought he was the lord of light and darkness and of the seasons is evidently due to his once supposed Godhead. The fire, too, which he is said to have kept burning may be the reminiscence of a sacrificial fire.

From a letter written to Sir Samuel Ferguson by the late Brian O'Looney, concerning Mount Callan in the Co. Clare, we see that this legend of Crom was widely circulated.

"Domnach Lunasa or Lammas Sunday," says O'Looney, the first Sunday of the month of August was the first fruits' day, and a great day on Buaile-na-greine. On Lammas Sunday, called Domnach Crom Dubh, and anglicised Garland Sunday, every householder was supposed to feast his family and household on the first fruits, and the farmer who failed to provide his people with new potatoes, new bacon and white cabbage on that day was called a felemuir gaoithe, or wind farmer; and if a man dug new potatoes before Crom Dubh's day he was considered a needy man The assemblage of this day was called comthineol Chruim Dhuibh, or the congregation or gathering of Crom Dubh, and the day is called from Mm Domnach Chrom Dubh, or Crom Dubh's Sunday, now called Garland Sunday by the English-speaking portion of the people of the surrounding districts. This name is supposed to have been derived from the practise of strewing garlands of flowers on the festive mound [or Mount Callan] on this day, as homage to Crom Dubh hence the name Garland Sunday. Assuredly I saw blossoms and flowers deposited upon it on the first Sunday of August, 1844, and put some upon it myself, as I saw done by those who were with me.

If you ask me who Crom Dubh was, I can only tell you I asked the question myself on the spot. I was told that Crom was a god and that Dubh or Dua meant a sacrifice, which in combination made Crom Dubh, or Crom Dua, that is, Crom's Sacrifice ; and this Sunday was set apart for the feast and commemoration of this Crom Dubh, whoever he may have been.

It is interesting to find O'1/ooney's old-time experiences in Co. Clare so far borne out by this legend from North Mayo.

The name Teideach given to Crom's son, is, as Mr. Lloyd acutely points out, founded upon a misunderstanding of the name of the hole which must have been "poll an t'seidte," the puffing or blowing hole. Downpatrick, where these events are supposed to have taken place, is at the extreme northern extremity of Tyrawley, Co. Mayo, and all the other places are in its neighbourhood.

For the leannun sidhe, or fairy sweetheart (often supposed to be the muse of the poets), see O' Kearney's " Feis tighe

Chonain." Oss. Soc. Publ. vol. II., pp. 80-103. For the Irish of this story, see " Lub na Caillighe," p. 33.

St. Patrick And Crom Dubh: The Story

Before St. Patrick came to Ireland there lived a chieftain in the Lower Country 1 in Co. Mayo, and his name was Crom Dubh. Crom Dubh lived beside the sea in a place which they now call Dun Patrick, or Downpatrick, and the name which the site of his house is called by is Dun Briste, or Broken Fort. My story will tell why it was called Dun Briste.

It was well and it was not ill, brother of my heart ! Crom Dubh was one of the worst men that could be found, but as he was a chieftain over the people of that country he had everything his own way ; and that was the bad way, for he was an evil-intentioned, virulent, cynical, 2 obstinate man, with desire to be avenged on every one who did not please him. He had two sons, Teideach and Clonnach, and there is a big hollow going in under the road at Gleann Lasaire, and the name of this hollow in Poll a' Teidigh or Teideach's hole, for it got its name from Crom Dubh's son, and the name of this hole is on the mouth of [i.e., used by] English-speaking people, though they do not know the meaning of it. Nobody knows how far this hole is going back under the glen, but it is said by the old Irish speakers that Teideach used to go every day in his little floating curragh into this hole under the glen, and that this is the reason it was called Teideach's Hole.

It was well, my dear. To continue the story, Crom 1 Lower means " northern." It means round the Lagan, Creevagh and Ballycastle.

2 Literally " doggish." The meaning is rather "snarling " or "fierce " than cynical.

LEGENDS OF SAINTS AND SINNERS;

Dubh's two sons were worse than himself, and that leaves them bad enough! Crom Dubh had two hounds of dogs and their names were Coinn lotair and Saidhthe Suaraighe,1 and if ever there were [wicked] mastiffs these two dogs were they. He had them tied to the two jaws of the door, in order to loose them and set them to attack people according as they might come that way; and, to go further, he had a big fire kindled on the brink of the cliff so that any one who might escape from the hounds he might throw into the fire ; and to make a long story short, the fame of Crom Dubh and his two sons, and his two mastiffs, went far and wide, for their evil- doing ; and the people were so terrified at his name, not to speak of himself, that they used to hide their faces in their bosoms when they used to hear it mentioned in their ears, and the people were so much afraid of him that if they heard the bark of a dog they would go hiding in the dwellings that they had underground, to take refuge in, to defend themselves from Crom Dubh and his mastiffs.

It is said that there was a linnaun shee or fairy sweetheart walking with Crom Dubh, and giving him knowledge according as he used to require it. In place of his inclining to what was good as he was growing in age, the way he went on was to be growing in badness every day, and the wind was not quicker than he, for he was as nimble as a March hare. When he used to go out about the country he used to send his two sons and his two mastiffs before him, and they announcing to the people according as

1 Pronounced like " Cunn eetir " and " sy-ha soory " hound of rage and bitch of wickedness

2 Linnaun shee, a fairy sweetheart; in Irish spelt "leannán sidhe."

ST. PATRICK AND CROM DUBH. 5

they proceeded, that Crom Dubh was coming to collect

his standing rent, and bidding them to have it ready for

him. Crom Dubh used to come after them, and his

trickster (?) along with him, and he drawing after him a

sort of yoke like a wheelless sliding car, and according

as he used to get his standing-rent it used to be thrown

into the car, and every one had to pay according to his

ability. Anyone who would refuse, he used to be brought

next day before Crom Dubh, as he sat beside the fire,

and Crom used to pass judgment upon him, and after the

judgment the man used to be thrown into the fire. Many

a plan and scheme were hatched against Crom Dubh to

put him out of the world, but he overcame them all, for

he had too much wizardry from the [fairy] sweetheart.

Crom Dubh was continuing his evil deeds for many

years, and according as the story about him remains

living and told from person to person, they say that he was

a native of hell in the skin of a biped, and through the horror

that the people of the country had for him they would

have given all that ever they saw if only Crom Dubh and

his company could have been put-an-end-to ; but there

was no help for them in that, since he and his company

had the power, and they had to endure bitter persecution

for years, and for many years, and every year it was

getting worse ; and they without any hope of relief because

they had no knowledge of God or Mary or of anything else

which concerned heaven. For that reason they could not

put trust in any person beyond Crom Dubh, because they

thought, bad as he was, that it was he who was giving

them the light of the day, the darkness of the night, and

the change of seasons.

6 LEGENDS OF SAINTS AND SINNERS.

It was well, brother of my heart. During this time

St. Patrick was going throughout Ireland, working dili-

gently and baptizing many people. On he went until

he came to Fo-choill or Foghill ; and at that time and for

long afterwards there were nothing but woods that grew

in that place, but there is neither branch nor tree there

now. However, to pursue the story, St. Patrick began

explaining to the Pagans about the light and glory of the

heavens. Some of them gave ear to him, but the most

of them paid him no attention. After he had taken all

those who listened to him to the place which was called

the Well of the Branch to baptize them, and when he had

them baptized, the people called the well Tobar Phadraig,

or Patrick's Well, and that is there ever since.

When these Pagans got the seal of Christ on their fore-

head, and knowledge of the Holy Trinity, they began

telling St. Patrick about the doings of Crom Dubh and his

evil ways, and they besought him if he had any power

from the All-mighty Father to chastise Crom Dubh,

rightly or wrongly, or to give him the Christian faith if

it were possible.

It was well, brother, St. Patrick passed on over through

Traigh Leacan, up Beal Tnighadh, down Craobhach, and

down under the Logan, the name that was on Crom

Dubh's place before St. Patrick came. When St. Patrick

reached the Logan, which is near the present Bally-

castle, he was within a quarter of a mile of Crom Dubh's

house, and at the same time Crom Dubh and Teideach

his son were trying a bout of wrestling with one another,

while Saidhthe Suaraighe was stretched out on the ground

from ear to tail. With the squeezing they were giving

ST. PATRICK AND CROM DUBH. 7

one another they never observed St. Patrick making

for them until Saidhthe Suaraighe put a howling bark

out of her, and with that the pair looked behind them and

they saw St. Patrick and his defensive company with

him, making for them ; and in the twinkling of an eye

the two rushed forward, clapping their hands and setting

Saidhthe Suaraighe at them and encouraging her.

With that Teideach put his fore finger into his mouth

and let a whistle calling for Coinn lotair, for she was at

that same time hunting with Clonnach on the top of Glen

Lasaire, and Glen Lasaire is nearly two miles from Dun

Phadraig, but she was not as long as while you'd be saying

De' raisias [Deo Gratias] coming from Glen Lasaire when

she heard the sound of the whistle. They urged the two

bitches against St. Patrick, and at the same time they did

not know what sort of man St. Patrick was or where he

came from.

The two bitches made for him and coals of fire out of

their mouths, and a blue venemous light burning in their

eyes, with the dint of venom and wickedness, but just as

they were going to seize St. Patrick he cut [marked] a ring

round about him with the crozier which he had in his

hand, and before the dogs reached the verge of the ring

St. Patrick spoke as follows :

A lock on thy claws, a lock on thy tooth,

A lock on Coinn lotair of the fury.

A lock on the son and on the daughter of Saidhthe Suaraighe.

A lock quickly, quickly on you.

Before St. Patrick began to utter these words there

was a froth of foam round their mouths, and their hair

was standing up as strong as harrow-pins with their fury,

8 LEGENDS OF SAINTS AND SINNERS.

but after this as they came nearer to St. Patrick they

began to lay down their ears and wag their tails. And

when Crom Dubh saw that, he had like to faint, because he

knew when they laid down their ears that they would not

do any hurt to him they were attacking. The moment

they reached St. Patrick they began jumping up upon

him and making friendly with him. They licked both

his feet from the top of his great toe 1 to the butt of his

ankle, and that affection [thus manifesting itself] is

amongst dogs from that day to this. St. Patrick began

to stroke them with his hand and he went on making

towards Crom Dubh, with the dogs walking at his heels.

Crom Dubh ran until he came to the fire and he stood up

beside the fire, so that he might throw St. Patrick

into it when he should come as far as it. But as St.

Patrick knew the strength of the fire beforehand he lifted

a stone in his hand, signed the sign of the cross on the

stone, and flung the stone so as to throw it into the middle

of the flames, and on the moment the fire went down to the

lowest depths of the ground, in such a way that the hole

is there yet to be seen, from that day to this, and it is called

Poll na Sean-tuine, the hole of the old fire (?), and when

the tide fills, the water comes in to the bottom of the hole,

and it would draw " deaf cows out of woods " the

noise that comes out of the hole when the tide is coming

in.

It was well, company 2 of the world ; when Crom Dubh

saw that the fire had departed out of sight, and that the dogs

had failed him and given him no help (a thing they had

1 Rather " the space between the toes."

2 A variant of "it was well, my dear."

ST. PATRICK AND CROM DUBH. 9

never done before), he himself and Teideach struck out

like a blast of March wind until they reached the house,

and St. Patrick came after them. They had not far to

go, for the fire was near the house. When St. Patrick

approached it he began to talk aloud with Crom Dubh,

and he did his best to change him to a good state of grace,

but it failed him to put the seal of Christ on his forehead,

for he would not give any ear to St. Patrick's words.

Now there was no trick of deviltry, druidism, witch-

craft, or black art in his heart, which he did not work for

all he was able, trying to gain the victory over St. Pat-

rick, but it was all no use for him, for the words of God

were more powerful than the deviltry of the fairy]

sweetheart.

With the dint of the fury that was on Crom Dubh and

on Teideach his son, they began snapping and grinding

their teeth, and so outrageous was their fury that St.

Patrick gave a blow of his crozier to the cliff under the

base of the gable of the house, and he separated that much

of the cliff from the cliffs on the mainland, and that is to

be seen there to-day just as well as the first day, and that

is the cliff that is called Dun Briste or Broken Fort.

To pursue the story. All that much of the cliff is a good

many yards out in the sea from the cliff on the mainland,

so Crom Dubh and his son had to remain there until

the midges and the scaldcrows had eaten the flesh off their

bones. And that is the death that Crom Dubh got, and

that is the second man that midges ate, 1 and our ancient

shanachies say that the first man that midges ate was Judas

1 See the story of Mary's Well, p. 17.

10 LEGENDS OF SAINTS AND SINNERS.

after he had hanged himself ; and that is the cause why the

bite of the midges is so sharp as it is.

To pursue the story still further. When Clonnach saw

what had happened to his father he took fright, and he

was terrified of St. Patrick, and he began burning the

mountain until he had all that side of the land set on fire.

So violently did the mountains take fire on each side of

him that himself could not escape, and they say that he

himself was burned to a lump amongst them.

St. Patrick returned back to Fochoill [Foghill] and round

through Baile na Pairce, the Town of the Field, and Bein

Buidhe, the Yellow Ben, and back to Clochar. The

people gathered in multitudes from every side doing

honourable homage to St. Patrick, and the pride of the

world on them that an end had been made of Crom Dubh.

There was a well near and handy, and he brought the

great multitude round about the well, and he never left

mother's son or man's daughter without setting on their

faces the wave of baptism and the seal of Christ on their

foreheads. They washed and scoured the walls of the well,

and all round about it, and they got forked branches and

limbs of trees and bound white and blue ribbons on them,

and set them round about the well, and every one of them

bowed down on his knees saying their prayers of thank-

fulness to God, and as an entertainment for St. Patrick

on account of his having put an end to the sway of Crom

Dubh.

After making an end of offering up their prayers every

man of them drank three sups of water out of the well,

and there is not a year from that out that the people

used not to make a turns or pilgrimage to the well, on the

ST. PATRICK AND CROM DUBH. II

anniversary of that day ; and that day is the last Sunday

of the seventh month, and the name the Irish speakers

call the month by in that place is the month of Lughnas

[August] and the name of the Sunday is Crom Dubh's

Sunday, but, the name that the English speakers call

the Sunday by, is Garland Sunday. There is never a

year from that to this that there does not be a meeting

in Cill Chuimin, for that is the place where the well is.

They come far and near to make a pilgrimage to the well ;

and a number of other people go there too, to amuse

themselves and drink and spend. And I believe that the

most of that rakish lot go there making a mock of the

Christian Irish-speakers who are offering up their prayers

to their holy patron Patrick, high head of their religion.

Cuimin's well is the name of this well, for its name was

changed during the time of Saint Cuimin on account of

all the miraculous things he did there, and he is buried

within a perch of the well in Cill Chuimin.

There does be a gathering on the same Sunday at

Dun Padraig or Downpatrick at the well which is called

Tobar Brighde or Briget's Well beside Cill Brighde, and

close to Dun Briste ; but, love of my heart, since the

English jargon began a short time ago in that place the

old Christian custom of the Christians is almost utterly

gone off.

There now ye have it as I got it, and if ye don't like it

add to it your complaints. 1

1 Apparently tell it with your complaint added to it.

View these photos in a gallery

View these photos in a gallery

_20-crop-u11671.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_4.jpg)

_8.jpg)

_11.jpg)

_10.jpg)

_14.jpg)

_283x55.jpg)

_483x55.jpg)

_883x55.jpg)

_1183x55.jpg)

_10-crop-u10066.jpg)

_1483x55.jpg)

_20688x461.jpg)

_2083x55.jpg)