Kilroe Church

Dating from Patrician times, it was once suggested by the late local historian, Rev. Dr. McDonnell, that because of the great number of brown-red sandstones used in the construction of the church it acquired its name-Kilroe-‘the Red Church,’ from which the surrounding area then got its name. But it is more likely that Cill Reo, anglicized as Kilroe, is in fact a corruption of ‘Reo’s Church,’ the site of a pre-Patrician sacred place inhabited by a hermit named ‘Reo.’

The respected nineteenth- century scholar and antiquarian Dr. John O’ Donovan was of the belief that Kilroe was one of the oldest, if not the oldest, of all stone church ruins in Ireland ‘not excepting even the Church of Bishop Mel at Ardagh.’

Added to which, it is also suggested in the local tradition that Kilroe may be the church where the relics of the two sister S.S. Crebrea/Crebriu and Lassara/ Lesru, were once venerated. Crebrea and Lassara were the daughters of Gleru who gave sanctuary to St. Patrick in Foghill when he was a fugitive from captivity and whose voices he heard in his vision dreams calling him back to Ireland.

The Life of St Patrick contains the following reference:

“And the man of God baptised in those parts the seven sons of Drogenius and selected one of them, Mac Erca, to be his own disciple; but seeing he was very much beloved by his parents, and that he durst not bring him to distant parts, he gave him over to be instructed by Bishop Bronius. He (MacEcra) is the person who ruled the Church of Kilroe Mór in the country of Amalgadia.” The sons of Drogenius were afterwards revered on 15 April in the Church of Kilroe.

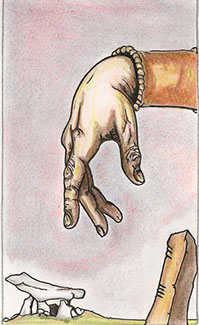

A local version of the tale tells that St. Patrick raised his hand and pointed out where the young cleric Mac Erca, the son of Mac Dregain (Drogenius) would have his church and afterwards his grave, and on that spot he erected a cross to mark the site, according to his custom. The place which St. Patrick thus pointed out is the old churchyard of Kilroe, over the estuary, about a half-mile north of Crosspatrick.

The aforementioned John O'Donovan writing in 1844 gives the following further description of the remains of Kilroe:

The aforementioned John O'Donovan writing in 1844 gives the following further description of the remains of Kilroe:

“A very ancient church in ruins, situated in a townland of the same name, in the parish of Killala...It stands on a rocky hillock about one mile to the east of the town of Killala...This church is built of very large stones, in the primitive Irish style, and is only 24’in length and 18’ in breadth. Its West gable and South wall are nearly destroyed, but the North wall and East gable, with its small round-headed window are in good preservation.” An earlier 1838 description of the ruins states “...being faced of large squarish stones and their interior filled with small pebbles cemented with very hard mortar of lime and sand, as appears from the South-East corner where the character of the masonry can be clearly seen. One stone in the external face of the North side-wall is 5’long and 20” high, and another near it is about 3’8” square.”

Added to which the Rev. Dr. Healy, in his 1905 publication, Patrick in the Plains of Mayo - The Life and Writings of St. Patrick with Appendices, Etc wrote:

Added to which the Rev. Dr. Healy, in his 1905 publication, Patrick in the Plains of Mayo - The Life and Writings of St. Patrick with Appendices, Etc wrote:

“It [Kilroe] is the only Patrician church of which even the remnant of a ruin now remains in Tirawley. The site was beautifully chosen on the very brow of a rocky encampment, whose base is washed by the waters of the high Spring tides when they sweep up the estuary of the river. A considerable portion of the south wall still remains built of very large stones with little or no mortar. The grey old walls still frown above the flood, and, doubtless, the bones of MacErca, as Patrick said, are now commingled with the dust of the old churchyard. The place is well worthy of a visit.”

Since those days the structure has suffered great decay and what now remains of this extremely rare and almost forgotten building may be found a little over 1km from Killala, on the ‘Old French Road’ close to Moyne Abbey. The remains are in such a disgraceful state of official dereliction and neglect that without previous knowledge of the location, it would be almost impossible for the visitor not to pass by it, never mind guess the origin of the “sacred rubble.”

The Irish words, cill, eaglais, teampull, domhnach,-all originally Latin, signify a church. Cill (kill) also written cell and ceall, is the Latin cella and next to baile, it is the most common root in Irish placenames and its most anglicised form is ‘kill’ or ‘kil.’

In fact, many of the terms employed in the Irish language to designate Christian structures, ceremonies and offices are derived directly from Latin. This came about because the early missionaries, finding no suitable words in the native tongue introduced the necessary Latin terms, which, with the passing of time, were considerably modified according to the laws of Irish pronunciation. For example words such as easpog, Old Irish, epsog, a bishop, comes from episcopus; saggart or sacart, a priest, from sacerados; beannacht, Old Irish, bendacht, a blessing from benedicto; Aiffrionn or Aiffrend, the Mass, from offerenda; and many others.

The Battle of Kilroe

During the latter part of the thirteenth century, most likely 1281, the locally famous Battle of Kilroe was fought between the invading force of “Welshmen” composed mainly of Barretts and their sub-tribes who had earlier taken and conquered Tirawley/Tyrawley, after which they expelled the native tribes, such as the O’Dowds and others, who then rallied to make a united challenge against them.

During the latter part of the thirteenth century, most likely 1281, the locally famous Battle of Kilroe was fought between the invading force of “Welshmen” composed mainly of Barretts and their sub-tribes who had earlier taken and conquered Tirawley/Tyrawley, after which they expelled the native tribes, such as the O’Dowds and others, who then rallied to make a united challenge against them.

While The Judicary Rolls and the Annals of Loch Cé both allude to the battle, neither mentions the particular cause or reason as to why it was fought. In The History of the County Mayo to the Close of the Sixteenth Century, Hubert Thomas Knox claims that the battle may have arisen “out of the claims of Adam Cusack and William Barrett of Bac and Glen to the land of Bredagh, under early de Burgo grants, which gave rise to litigation in 1253.”

The main group of invaders were led by William Mór Barrett. He had previously defeated another batch of adventurers, including the Cusacks, Browns and Moores, after which he claimed and held their fortified castle and lands at Meelick, near Killala, before bestowing them upon his kinsman Mac Wattin. Meelick, in Irish Míleac, translates alternatively as ‘low-lying marshy land,’ or ‘an isolated piece of land,’-there are more than thirty townlands in county Mayo bearing this name.

Incensed, and seeking revenge upon Barrett for the loss of his lands and castle, Adam Cusack sought the aid of several local clans and quickly struck up a volatile alliance with the influential but dispossessed chieftain, Taichlech “Tahilly” O’Dowd.

The opposing forces were initially drawn up in the vicinity of the present-day Moyne Abbey, and local lore still identifies the easily spotted pillar stones as marking the positions of the armies. Even though these stones pre-date the battle by centuries, there is a traditional belief that because of their prominence they may well have been used as battle-markers during this particular action.

The lore further maintains that before the battle proper commenced, Adam Cusack and William Mór Barrett rode out and at the head of their respective forces, and met in conference to discuss possible terms for an armistice. Unfortunately, during the parley an un-named archer accidently shot an arrow into the opposing ranks (the lore fails to mention from which side the arrow was fired), whereupon both armies fell upon each other.

It is told that during the ensuing battle, Taichlech O’Dowd and his friend and ally Taichlech O’Boyle were foremost in bravery and daring. The tradition further tells that in the midst of the affray William Mór Barrett was severely wounded and taken prisoner (he later died in one of Cusack’s dungeons) and several of his principal lieutenants, including Adam Fleming slain, after which their supporters fled in disarray and despair leaving Cusack and O’Dowd’s army to carry the day. Many of those who fled the field sought sanctuary in the grounds of the nearby Church of Kilroe, but were pursued there by the troops of the vengeful victors, before being surrounded and butchered unmercifully.

It is told that during the ensuing battle, Taichlech O’Dowd and his friend and ally Taichlech O’Boyle were foremost in bravery and daring. The tradition further tells that in the midst of the affray William Mór Barrett was severely wounded and taken prisoner (he later died in one of Cusack’s dungeons) and several of his principal lieutenants, including Adam Fleming slain, after which their supporters fled in disarray and despair leaving Cusack and O’Dowd’s army to carry the day. Many of those who fled the field sought sanctuary in the grounds of the nearby Church of Kilroe, but were pursued there by the troops of the vengeful victors, before being surrounded and butchered unmercifully.

The tawdry alliance between Cusack and O’Dowd was not destined for permanence and the year following the battle, O’Dowd was murdered by Cusack on the Strand of Ballysadare, in modern, county Sligo. Cusack was later defeated by another Norman family, the de Burghs/Burgos, present day Burkes.

A short distance from Crosspatrick, in the direction of Killala, the ruins of an Anglo Norman Castle are visible at the aforementioned Meelick. Situated to the west of the road, this is the castle attributed to Adam Cusack. It was once known as Caiseail Bearnach-‘The Castle of the Gap,’ and as referenced, it also became the stronghold of another Anglo Norman family the Barretts. To consolidate their positions, the Normans and Anglo Normans built many strong castles throughout the country, most especially between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and while few examples of these structures remain in this area today, it is known that Norman castles were located at Killala, Meelick, Carrickanass, Castlereagh, Ballycastle, Ballysakeery, Deel, Enniscoe, Belleek and Castlelacken.

The Welshmen Of Tirawley By Samuel Ferguson, Ll.D., M.R.I.A.

Several Welsh families, associates in the invasion of Strongbow, settled in the west of Ireland. Of these, the principal, whose names have been preserved by the Irish antiquarians, were the Walshes, Joyces, Heils (a quibus MacHale), Lawlesses, Tolmyns, Lynotts, and Barretts, which last draw their pedigree from Walynes, son of Guyndally, the Ard Maor, or High Steward of the Lordship of Camelot, and had their chief seats in the territory of the two Bacs, in the barony of Tirawley, and county of Mayo. Clochan-na-n'all, i.e., “The Blind Men's Steppingstones,” are still pointed out on the Duvowen river, about four miles north of Crossmolina, in the townland of Garranard; and Tubber-na-Scorney, or “Scrags Well,” in the opposite townland of Carns, in the same barony. For a curious terrier or applotment of the MacWilliam's revenue, as acquired under the circumstances stated in the legend preserved by MacFirbis, see Dr. O'Donovan's highly-learned and interesting “Genealogies, &c. of Hy Fiachrach,” in the publications of the Irish Archæological Society--a great monument of antiquarian and topographical erudition.

Scorney Bwee, the Barrett’s bailiff, lewd and lame,

To lift the Lynott’s taxes when he came,

Rudely drew a young maid to him;

Then the Lynotts rose and slew him,

And in Tubber-na-Scorney threw him--

Small your blame,

Sons of Lynott!

Sing the vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley.

Then the Barretts to the Lynotts gave a choice,

Saying, “Hear, ye murderous brood, men and boys,

Choose ye now, without delay,

Will ye lose your eyesight, say,

Or your manhoods here to-day?”

Sad your choice,

Sons of Lynott!

Sing the vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley.

Then the little boys of the Lynotts, weeping, said,

“Only leave us our eyesight in our head.”

But the bearded Lynotts then

Quickly answered back again,

“Take our eyes, but leave us men,

Alive or dead,

Sons of Wattin!”

Sing the vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley.

So the Barretts, with sewing-needles sharp and smooth,

Let the light out of the eyes of every youth,

And of every bearded man,

Of the broken Lynott clan;

Turning south

To the river--

Sing the vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley.

O'er the slippery stepping-stones of Clochan-na-n’all

They drove them, laughing loud at every fall,

As their wandering footsteps dark

Failed to reach the slippery mark,

And the swift stream swallowed stark,

One and all,

As they stumbled--

Sing the vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley.

Out of all the blinded Lynotts, one alone

Walked erect from stepping-stone to stone;

So back again they brought you,

And a second time they wrought you

With their needles; but never got you

Once to groan,

Emon Lynott,

For the vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley.

But with promt-projected footsteps sure as ever,

Emon Lynott again crossed the river,

Though Duvowen was rising fast,

And the shaking stones o'ercast

By cold floods boiling past;

Yet you never,

Emon Lynott,

Faltered once before your foemen of Tirawley;

But, turning on Ballintubber bank, you stood,

And the Barretts thus bespoke o'er the flood--

“Oh, ye foolish sons of Wattin,

Small amends are these you’ve gotten,

For, while Scorney Bwee lies rotten,

I am good

For vengeance!”

Sing the vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley.

“For ‘tis neither in eye nor eyesight that a man

Bears the fortunes of himself or of his clan;

But in the manly mind

And in loins with vengeance lined,

That your needles could never find,

Though they ran

Through my heartstrings!”

Sing the vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley.

“But, little your women’s needles do I reck;

For the night from heaven never so black,

But Tirawley, and abroad

From the Moy to Cuan-an-fod,

I could walk it every sod,

Path and track,

Ford and togher,

Seeking vengeance on you, Barretts of Tirawley?

“The night when Dathy O'Dowda broke your camp,

What Barrett among you was it held the lamp--

Showed the way to those two feet,

When through wintry wind and sleet,

I guided your blind retreat

In the swamp

Of Beäl-an-asa?

O ye vengeance-destined ingrates of Tirawley!”

So leaving loud-shriek-echoing Garranard,

The Lynott like a red dog hunted hard,

With his wife and children seve,

‘Mong the beasts and fowls of heaven

In the hollows of Glen Nephin,

Light-debarred,

Made his dwelling,

Planning vengeance on the Barretts of Tirawley.

And ere the bright-orb’d year its course had run,

On his brown round-knotted knee he nursed a son,

A child of light, with eyes

As clear as are the skies

In summer, when sunrise

Has begun;

So the Lynott

Nursed his vengeance on the Barretts of Tirawley.

And, as ever the bright boy grew in strength and size,

Made him perfect in each manly exercise,

The salmon in the flood,

The dun deer in the wood,

The eagle in the cloud,

To surprise,

On Ben Nephin,

Far above the foggy fields of Tirawley.

With the yellow-knotted spear-shaft, with the bow,

With the steel, prompt to deal shot and blow,

He taught him from year to year,

and trained him, without a peer,

For a perfect cavalier,

Hoping so--

Far his forethought--

For vengeance on the Barretts of Tirawley.

And, when mounted on his proud-bounding steed,

Emon Oge sat a cavalier indeed;

Like the ear upon the wheat

When winds in autumn beat

On the bending stems, his seat;

And the speed

Of his courser

Was the wind from Barna-na-gee o’er Tirawley!

Now when fifteen sunny summers thus were spent,

(He perfected in all accomplishment)--

The Lynott said, “My child,

We are over long exiled

From mankind in this wild--

Time we went

O’er the mountain

To the countries lying over-against Tirawley.”

So out over mountain-moors, and mosses brown,

And green stream-gathering vales, they journeyed down;

Till, shining like a star,

Through the dusky gleams afar,

The bailey of Castlebar,

And the town

Of MacWilliam

Rose bright before the wanderers of Tirawley.

“Look sowthward, my boy, and tell me as we go,

What see’st thou by the loch-head below.”

“Oh, a stone-house strong and great,

And a horse-host at the gate,

And a captain in armour of plate--

Grand the show!

Great the glancing!

High the heroes of this land below Tirawley!

“And a beautiful Bantierna by his side,

Yellow gold on all her gown-sleeves wide;

And in her hand a pearl

Of a young, little, fair-haired girl--

Said the Lynott, “It is the Earl!

Let us ride

To his presence.”

And before him came the exiles of Tirawley.

“God save thee, MacWilliam,” the Lynott thus began;

“God save all here besides of this clan;

For gossips dear to me

Are all in company--

For in these four bones ye see

A kindly man

Of the Britons--

Emon Lynott of Garranard of Tirawley.

“And hither, as kindly gossip-law allows,

I come to claim a scion of thy house

To foster, for thy race,

Since William Conquer's [1] days,

Have ever been wont to place,

With some spouse

Of a Briton,

A MacWilliam Oge, to foster in Tirawley.

“And to show thee in what sort our youth are taught

I have hither to thy home of valour brought

This one son of my age,

For a sample and a pledge

For the equal tutelage,

In right thought,

Word, and action,

Of whatever son ye give into Tirawley."

Then MacWilliam beheld the brave boy ride and run,

Saw the spear-shaft from his white shoulder spun--

With a sigh, and with a smile,

He said,--"I would give the spoil

Of a county, that Tibbot Moyle,

My own son,

Were accomplished

Like this branch of the kindly Britons of Tirawley."

When the Lady MacWilliam she heard him speak,

And saw the ruddy roses on his cheek,

She said, "I would give a purse

Of red gold to the nurse

That would rear my Tibbot no worse;

But I seek

Hitherto vainly--

Heaven grant that I now have found her in Tirawley!"

So they said to the Lynott, "Here, take our bird!

And as pledge for the keeping of thy word,

Let this scion here remain

Till thou comest back again:

Meanwhile the fitting train

Of a lord

Shall attend thee

With the lordly heir of Connaught into Tirawley."

So back to strong-throng-gathering Garranard,

Like a lord of the country with his guard,

Came the Lynott, before them all,

Once again over Clochan-na-n'all,

Steady-striding, erect, and tall,

And his ward

On his shoulders;

To the wonder of the Welshman of Tirawley.

Then a diligent foster-father you would deem

The Lynott, teaching Tibbot, by mead and stream,

To cast the spear, to ride,

To stem the rushing tide,

With what feats of body beside,

Might beseem

A MacWilliam,

Fostered free among the Welshmen of Tirawley.

But the lesson of hell he taught him in heart and mind,

For to what desire soever he inclined,

Of anger, lust, or pride,

He had it gratified,

Till he ranged the circle wide

Of a blind

Self-indulgence,

Ere he came to youthful manhood in Tirawley.

Then, even as when a hunter slips a hound,

Lynott loosed him--God's leashes all unbound--

In pride of power and station,

And the strength of youthful passion,

On the daughters of thy nation,

All around

Wattin Barrett!

Oh! the vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley!

Bitter grief and burning anger, rage and shame,

Filled the houses of the Barretts where'er he came;

Till the young men of the Bac

Drew by night upon his track,

And slew him at Cornassack--

Small your blame,

Sons of Wattin!

Sing the vengeance of the Welshmen of Tirawley.

Said the Lynott, "The day of my vengeance is drawing near,

The day for which, through many a long dark year,

I have toiled through grief and sin--

Call ye now the Brehons in,

And let the plea begin

Over the bier

Of MacWilliam,

For an eric upon the Barretts of Tirawley."

Then the Brehons to MacWilliam Burk decreed

An eric upon Clan Barrett for the deed;

And the Lynott's share of the fine,

As foster-father, was nine

Ploughlands and nine score kine;

But no need

Had the Lynott,

Neither care, for land or cattle in Tirawley.

But rising, while all sat silent on the spot,

He said, "The law says--doth it not?--

If the foster-sire elect

His portion to reject,

He may then the right exact

To applot

The short eric."

"'Tis the law," replied the Brehons of Tirawley.

Said the Lynott, "I once before had a choice

Proposed me, wherein law had little voice:

But now I choose, and say,

As lawfully I may,

I applot the mulct to-day;

So rejoice

In your ploughlands

And you cattle which I renounce throughout Tirawley.

"And thus I applot the mulct: I divide

The land throughout Clan Barrett on every side

Equally, that no place

May be without the face

Of a foe of Wattin's race--

That the pride

Of the Barretts

May be humbled hence for ever throughout Tirawley.

"I adjudge a seat in every Barrett's hall

To MacWilliam: in every stable I give a stall

To MacWilliam: and, beside,

Whenever a Burke shall ride

Through Tirawley, I provide

At his call

Needful grooming,

Without charge from any Brughaidh of Tirawley.

"Thus lawfully I avenge me for the throes

Ye lawlessly caused me and caused those

Unhappy shame-faced ones

Who, their mothers expected once,

Would have been the sires of sons--

O'er whose woes

Often weeping,

I have groaned in my exile from Tirawley.

"I demand not of you your manhoods, but I take--

For the Burks will take it--your Freedom! for the sake

Of which all manhood's given

And all good under heaven,

And, without which, better even

You should make

Yourselves barren,

Than see your children slaves throughout Tirawley!

"Neither take I your eyesight from you; as you took

Mine and ours: I would have you daily look

On one another's eyes

When the strangers tyrannize

By your hearths, and blushes arise,

That ye brook

Without vengeance

The insults of troops of Tibbots throughout Tirawley!

"The vengeance I designed, now is done,

And the days of me and mine nearly run--

For, for this, I have broken faith,

Teaching him who lies beneath

This pall, to merit death;

And my son

To his father

Stands pledged for other teaching in Tirawley."

Said MacWilliam--"Father and son, hang them high!"

And the Lynott they hanged speedily;

But across the salt-sea water,

To Scotland with the daughter

Of MacWilliam--well you got her!--

Did you fly,

Edmund Lindsay,

The gentlest of all the Welshmen of Tirawley!

'Tis thus the ancient Ollaves of Erin tell

How, through lewdness and revenge, it befel

That the sons of William Conquer

Came over the sons of Wattin,

Throughout all the bounds and borders

Of the land of Auley MacFiachra;

Till the Saxon Oliver Cromwell

And his valiant, Bible-guided,

Free heretics of Clan London

Coming in, in their succession,

Rooted out both Burk and Barrett,

And in their empty places

New stems of freedom planted,

With many a goodly sapling

Of manliness and virtue;

Which wile their children cherish

Kindly Irish of the Irish,

Neither Saxons nor Italians,

May the mighty God of Freedom

Speed them well,

Never taking

Further vengeance on his people of Tirawley!

[Note by the Editor, 1869: The author of this spirited Ballad in republishing The Welshmen of Tirawley in his "Lays of the Western Gael," p. 70, has changed several lines, some of them being among the most vigorous in the poem. For the purposes of comparison, I have thought it would be more interesting to give the ballad as it originally appeared.]

View these photos in a gallery

East gable of Kilroe Church, 1838