Tobar Mhuire - ‘Mary’s Well’

Beneath its spreading branches lay,

Deep, clear and still, a crystal well

Where monks would oft their aves say,

And pilgrims would their rosaries tell.

(Anon)

A short distance to the south of the Abbey of Rosserk, in a sacred space near the confluence of the Rosserk river and the estuary of the mighty and revered river Moy, a ‘Holy Well’ known as Tobar Mhuire/Tubbermuire –‘Mary’s Well’ may be found.

A short distance to the south of the Abbey of Rosserk, in a sacred space near the confluence of the Rosserk river and the estuary of the mighty and revered river Moy, a ‘Holy Well’ known as Tobar Mhuire/Tubbermuire –‘Mary’s Well’ may be found.

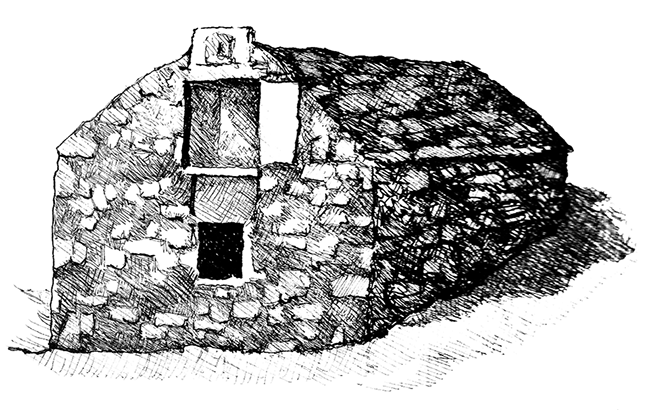

Once a popular place of great veneration, local folklore tells that an apparition of the Virgin Mary occurred here around the year 1680. A little stone vaulted building stands over the well bearing the following inscription: “This chapel was built in honour of the Blessed Virgin in the year of Our Lord 1799 by John Lynott of Roserk.” Beneath the inscription is the carved figure of a dove or robin bordered either side with the motto “Peace and Love,” under which are two Latin inscriptions. This construction stands on the site of an earlier one and contains a stone marked with the year 1654 or 1684.

The top Latin inscription reads: “Pax, &c., and after it “Amon.” Lower down and still in Latin;-“Discite justitiam moniti et non temnere divis mortem non timeo mons est in limine nostro Decessem a mundo velut umbra sol 1810”. This may translate as: “Be warned and learn to be righteous and not despise the divine. I do not fear death which is at our door. I would depart this world like a shadow of the sun 1810.” Alternatively, “Pursue justice, then you shall have no fear of God or death.”

The top Latin inscription reads: “Pax, &c., and after it “Amon.” Lower down and still in Latin;-“Discite justitiam moniti et non temnere divis mortem non timeo mons est in limine nostro Decessem a mundo velut umbra sol 1810”. This may translate as: “Be warned and learn to be righteous and not despise the divine. I do not fear death which is at our door. I would depart this world like a shadow of the sun 1810.” Alternatively, “Pursue justice, then you shall have no fear of God or death.”

The bottom slab from a preceding building bears the inscription in better Latin: “In honorem Di omnipotentis Beatissimae Virginis sine labe conceptae & omnium Sanctorum Caelestis Curiae me fieri fecit pater Moriatus Crehn August+30,1684.” –Possibly:- “Father Moriartus Crehn had me made, 30/8/1684, in honour of Almighty God and the Most Blessed Virgin Conceived Without Sin, and all the Saints of the Heavenly Court.”

There is an extant local story associated with the aforementioned inscription which tells that in 1869, the then Archbishop of Tuam, the formidable John McHale, attended the First Vatican Council in Rome, during which the Pontiff, Pope Pius X1, proclaimed the dogma of the immaculate conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The story maintains that rising to his feet, the Archbishop proudly addressed the Pontiff and informed him that the dogma would not present a problem to the people of the West of Ireland, because it was already inscribed in stone over a “Holy Well” dedicated to the Virgin in the Diocese of Killala.

In ancient days the Druids not only venerated but worshipped the clear water fountains which gushed from the earth, and it is told that they foretold the future by gazing into these sacred springs, that is, after the wells had been stirred by a wand of oak or mistletoe. This is the magic wand known in Irish as ‘Slat-Draoidheachta.’ Later, about the fifth century, with the coming of “organised” Christianity to Ireland, these wells were adopted, blessed and consecrated by the Christian evangelicals. Consequently, for centuries afterwards they were then greatly revered as “Holy” and became places of annual pilgrimage. Unsurprisingly, some of the well customs that have descended to this day would appear to be undoubted vestiges of pagan adoration.

After the general spread of Christianity throughout Ireland, the people’s affection for these wells was not only retained but intensified: most of the early Christian preachers established their humble foundations beside these fountains whose waters at the same time supplied the daily needs of the communities and served for the baptism of converts. In this manner did the pagan beliefs dwindle as many of our early saints and important Christian personalities became associated with wells, hundreds of which still retain their names.

This relic of ancient Pagan and Christian devotion whose waters were credited with curative powers, most especially with eyesight, had its own Pattern/Patron Day, 15 August, the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin. Each year for centuries past, on this particular day a special ‘Station’ or ecclesiastical ritual was performed at the well. It is recorded that families and relatives, many barefoot, generally performed the ritual as one unit, all praying silently, and unlike today, money, rags, or religious icons, were not left as “offerings,” mainly simple gifts such as horse-shoe nails, round iron nails, or small pieces of metal. The offerings were left so that any ailment the pilgrim might have would be left at the well and the ailment cured.

This relic of ancient Pagan and Christian devotion whose waters were credited with curative powers, most especially with eyesight, had its own Pattern/Patron Day, 15 August, the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin. Each year for centuries past, on this particular day a special ‘Station’ or ecclesiastical ritual was performed at the well. It is recorded that families and relatives, many barefoot, generally performed the ritual as one unit, all praying silently, and unlike today, money, rags, or religious icons, were not left as “offerings,” mainly simple gifts such as horse-shoe nails, round iron nails, or small pieces of metal. The offerings were left so that any ailment the pilgrim might have would be left at the well and the ailment cured.

In times gone by it was also not unusual for “drunkenness, fighting, and debauchery” to break out at these wells when the pious practices had been completed. Apart from the aforementioned activities some intrepid locals also saw these pilgrimages as a way to make money, and a correspondent writing in The Holy Wells of Ireland in 1836 was horrified to find two west of Ireland women ‘handing out water from a well as fast as they could, and being paid a halfpenny from each pilgrim in return for about half a pint.’

“Pilgrimages to wells are frequent to this day. The times are fixed for them; as the first of February, in honour of Tober Brigid, or St. Bridget's well, of Sligo. The bushes are draped with offerings, and the procession must move round as the sun moves, like the heathen did at the same spot so long ago. At Tober Choneill, or St. Connell's well, the correct thing is to kneel, then wish for a favour, drink the water in silence, and quietly retire, never telling the wish, if desiring its fulfilment.

“Pilgrimages to wells are frequent to this day. The times are fixed for them; as the first of February, in honour of Tober Brigid, or St. Bridget's well, of Sligo. The bushes are draped with offerings, and the procession must move round as the sun moves, like the heathen did at the same spot so long ago. At Tober Choneill, or St. Connell's well, the correct thing is to kneel, then wish for a favour, drink the water in silence, and quietly retire, never telling the wish, if desiring its fulfilment.

Unfortunately, these pilgrimages-often to wild localities-are attended with characteristic devotion to whiskey and free fights. At the Holy Well, Tibber, or Tober, Quan, the water is first soberly drunk on the knees. But when the whiskey, in due course, follows, the talking, singing, laughing, and love-making may be succeeded by a liberal use of the blackthorn.”

(Irish Druids and Old Irish Religions, 1894)

While trying to ascertain what if anything else motivated the people to visit Holy Wells, apart that is from personal cures, the Rev Charles O’ Connor, a noted 18th century antiquarian interviewed an old native of the west of Ireland man named Owen Hester and asked him to explain the reasoning behind the various phenomena and practices of leaving “offerings” at Holy Wells.

His answer was that “their ancestors always did it: that it was a preservative against the Geasu-Draoidacht, i.e. the sorceries of the Druids: that their cattle were preserved by it from infections and disorders; that the Daoine Maeithe, i.e. the fairies, were kept in good humour by it: and so thoroughly persuaded were they of the sanctity of those pagan practices that they would travel bareheaded and barefoot from ten to twenty miles for the purposes of crawling on their knees round these wells… westward as the sun travels, some three times, some six, some nine, and so on, in uneven numbers until their voluntary penances were completely fulfilled.”

It was once said that ‘so wet a country as Ireland should have so great a reverence for wells, is an evidence how early the primitive and composite races there came under the moral influence of oriental visitors and rulers, who had known in their native lands the want of rain, the value of wells. So deep was this respect, that by some the Irish were known as the People of Wells.’

In Irish Druids and Old Irish Religions, the author John Bonwick had this to say in relation to well-worship:

“In remote ages and realms, worship has been celebrated at fountains or wells. They were dedicated to Soim in India. Sopar-soma was the fountain of knowledge. Oracles were delivered there. But there were Cursing as well as Blessing wells.

Wells were feminine, and the feminine principle was the object of adoration there, though the specific form thereof changed with the times and the faith. In Christian lands they were dedicated, naturally enough, to the Virgin Mary. It is, however, odd to find a change adopted in some instances after the Reformation. Thus, according to a clerical writer in the Graphic, 1875, a noted Derbyshire well had its annual festival on Ascension Day, when the place was adorned with crosses, poles, and arches. All was religiously done in honour of the Trinity, the vicar presiding. Catholic localities still prefer to decorate holy wells on our Lady’s Assumption Day.

Wells were feminine, and the feminine principle was the object of adoration there, though the specific form thereof changed with the times and the faith. In Christian lands they were dedicated, naturally enough, to the Virgin Mary. It is, however, odd to find a change adopted in some instances after the Reformation. Thus, according to a clerical writer in the Graphic, 1875, a noted Derbyshire well had its annual festival on Ascension Day, when the place was adorned with crosses, poles, and arches. All was religiously done in honour of the Trinity, the vicar presiding. Catholic localities still prefer to decorate holy wells on our Lady’s Assumption Day.

It was in vain that the Early Church, the Mediaeval Church, and even the Protestant Church, sought to put down well-worship, the inheritance of extreme antiquity. Strenuous efforts were made by Councils. That of Rouen in the seventh century declared that offerings made there in the form of flowers, branches, rags, &c., were sacrifices to the devil. Charlemagne issued in 789 his decree against it—as did our Edgar and Canute.

As Scotland caught the infection by contact with Ireland, it was needful for the Presbyterian Church to restrain the folly. This was done by the Presbytery of Dingwall in 1656, though even worse practices were then condemned; as, the adoration of stones, the pouring of milk on hills, and the sacrifice of bulls. In 1628 the Assembly, prohibiting visits to Christ's well at Falkirk on May mornings, got a law passed sentencing offenders to a fine of twenty pounds Scot, and the exhibition in sackcloth for three Sundays in church. Another act put the offenders in prison for a week on bread and water.

Mahomet even could not hinder the sanctity attached to the well Zamzam at Mecca. More ancient still was holy Beersheba, the seven wells. Wales, especially North Wales, so long and intimately associated with Ireland, had many holy wells; as St. Thecla’s at Llandegla, and St. Winifrede’s of Flintshire Holywell. St. Madron’s well was useful in testing the loyalty of lovers. St. Breward’s well cured bad eyes, and received offerings in cash and pins. St. Cleer's was good for nervous ailments, and benefited the insane. The Druid magician Tregeagle is said still to haunt Dozmare Pool. Henwen is the Old Lady Well. The Hindoo Vedas proclaim that “all healing power is in the waters.”

Hydromancy, or divination by the appearance of water in a well, is cherished to the present time. One Christian prayer runs thus:—

Hydromancy, or divination by the appearance of water in a well, is cherished to the present time. One Christian prayer runs thus:—

“Water, water, tell me truly,

Is the man that I love duly,

On the earth, or under the sod,

Sick or well-in the name of God.”

Irish wells have been re-baptised, and therefore retain their sanctity. A stout resistance to their claims seems to have been made awhile by the early missionaries, since St. Columba exorcised a demon from a well possessed by it. They all, however, liked to resort to wells for their preaching stations. In one of the Lives of St. Patrick, it is related that “he preached at a fountain (well) which the Druids worshipped as a God.”

Milligan assures us, “The Celtic tribes, starting from hot countries, where wells were always of the utmost value, still continued that reverence for them which had been handed down in their traditions." This opinion may be controverted by ethnologists. But Croker correctly declares that even now in Ireland,” near these wells little altars or shrines are frequently constructed, often in the rudest manner, and kneeling before them, the Irish peasant is seen offering up his prayers.”

Milligan assures us, “The Celtic tribes, starting from hot countries, where wells were always of the utmost value, still continued that reverence for them which had been handed down in their traditions." This opinion may be controverted by ethnologists. But Croker correctly declares that even now in Ireland,” near these wells little altars or shrines are frequently constructed, often in the rudest manner, and kneeling before them, the Irish peasant is seen offering up his prayers.”

It is not a little singular that these unconfined Irish churches should be in contiguity with Holy Oaks or Holy Stones. Prof. Harttung, in his Paper before the Historical Society, remarked of the Irish-“They have from time immemorial been inclined to superstition.” He even believed in their ancient practice of human sacrifices.

In the story of the Well of Kilmore is an allusion to mystical fishes. An old writer says, “They do call the said fishes Easa Seant, that is to say, holie fishes.” In the charming poem of Diarmuid, there is an account of the Knight of the Fountain, and the sacred silver cup from which the pilgrim drank.

Giraldus, the Welsh Seer, beheld a man washing part of his head in the pool at the top of Slieve Gullion, in Ireland, when the part immediately turned grey, the hair having been black before. The opposite effect would be a virtue.

Prof. Robertson Smith, while admitting Well-worship as occurring with the most primitive of peoples, finds it connected with agriculture, when the aborigines had no better knowledge of a God. The source of a spring, said he, “is honoured as a Divine Being, I had almost said a divine animal.” “Such springs,” remarks Rhys, “have in later times been treated as Holy Wells.”

Prof. Robertson Smith, while admitting Well-worship as occurring with the most primitive of peoples, finds it connected with agriculture, when the aborigines had no better knowledge of a God. The source of a spring, said he, “is honoured as a Divine Being, I had almost said a divine animal.” “Such springs,” remarks Rhys, “have in later times been treated as Holy Wells.”

Wells varied in curative powers. St. Tegla’s was good for epilepsy. Rickety children benefit from a thrice dipping. Some, by the motion of the waters when something is thrown in, will indicate the coming direction of wind. Some will cure blindness, like that at Rathlogan, while others will cause it, except to some favoured mortals.

Offerings must be made to the spirit in charge of the well, and to the priestess acting as guardian. If in any way connected with the person, so much the better. A piece of a garment, money touched by the hand, or even a pin from clothes, is sufficient. Pins should be dropped on a Saint’s day, if good luck be sought. As Henderson's Folklore remarks, “The country girls imagine that the well is in charge of a fairy, or spirit, who must be propitiated by some offering.” Some well-spirits, as Peg O’Nell of the Ribble, can be more than mischievous. Besides the dropping of metal, or the slaughter of fowls, a cure requires perambulation, sunwise, three times round the well. On Saints’ day wells are often dressed with flowers.

Otway has asserted that “no religious place in Ireland can be without a holy well.” But Irish wells are not the only ones favoured with presents of pins and rags, for Scotland, as well as Cornwall and other parts of England, retain the custom. Mason names some rag-wells:—Ardclines of Antrim, Erregall-Keroge of Tyrone, Dungiven, St. Bartholomew of Waterford, St. Brigid of Sligo.

The spirits of the wells may appear as frogs or fish. Gomme, who has written so well on this subject, refers to a couple of trout, from time immemorial, in the Tober or well Kieran, Meath. Of two enchanted trout in the Galway Pigeon Hole, one was captured. As it immediately got free from the magic, turning into a beautiful young lady, the fisher, in fright, pitched it back into the well. Other trout-protected wells are recorded. Salmon and eels look after Tober Monachan, the Kerry well of Ballymorereigh. Two black fish take care of Kilmore well. That at Kirkmichael of Banff has only a fly in charge.

“The point of the legend is,” writes Robertson Smith, “that the sacred source is either inhabited by a demoniac being, or imbued with demoniac life.” It is useful, in the event of a storm near the coast, to let off the water from a well into the sea. This draining off was the practice of the Islanders of Innis Murray. The Arran Islanders derive much comfort from casting into wells flint-heads used by their forefathers in war. Innis Rea has a holy well near the Atlantic.

What was the age of Well-worship? The President of the Folklore Society, who deems the original worshippers Non-Aryan, i.e. before Celts came to Ireland, identifies the custom with the erection of stone circles. The scientific anthropologist, General Pitt-Rivers, tells us, “It is impossible to believe that so singular a custom as this, invariably associated with cairns, megalithic monuments, holy wells, or some such early Pagan institutions, could have arisen independently in all these countries.”

Enough has been said to show, as Wood-Martin observes, that Water-worship, recommended by Seneca, tolerated by the Church in times of yore, is a cult not yet gone out.”

The Tobair Mhuire Station which is preserved locally is as follows:

1. Begin at the rear of the well. Recite: seven Aves, one Gloria, one Creed-circle the well three times.

2. Move to the five mounds. At each of the five mounds recite: five Aves, one Gloria, one Creed-circle each mound three times.

3. Move to front of well. Recite: ten Aves, one Gloria and one Creed.

4. Great Circle: Complete the great circle by making three circuits of the entire station including the well and the five mounds while reciting the rosary.

5. The Well: Pray at the front of the well and bless with the water.

A “Sacred” thorn-tree can be seen growing from the roof of the small building. Thorn trees have a long association with Holy Wells, and the custom of erecting stone vaults over Holy Wells was once widespread throughout the country and many fine examples can still be seen in the locality, for example at Rathfran and Kilcummin.

“The Holy wells—the living wells—the cool, the fresh, the pure,

A thousand ages rolled away, and still those founts endure.”

(J.D. Frazer)

The ancient Irish word Neimheadh meant a sacred place or person or thing; one having the franchise of the Féine, a poet or learned person, and was commonly used when describing or referencing a sacred grove or sanctuary.

The ancient Irish word Neimheadh meant a sacred place or person or thing; one having the franchise of the Féine, a poet or learned person, and was commonly used when describing or referencing a sacred grove or sanctuary.

The esteemed folklorist, the late Dáithí o hOgáin maintains that the Neimheadh is a derivative of the old Celtic word ‘Nemeton’ which was used to describe a spiritual meeting place of learning, creativity, knowledge, reflection and succour- a sacred clearing in a wood or sacred grove. The word recurs throughout the Celtic world, from the Galatian, Drunemeton (sacred oakgrove in modern Turkey) to Nemetobriga in Spain and Aquae Nemetobriga, the Sacred Spring, at Buxton in Derbyshire. The old Irish fidnemed refers to a shrine in a forest. These spiritual centres underwent a metamorphosis of sorts with the coming of Christianity; but if they did they still retained their original purpose-the search for knowledge, truth and learning.

'Meon na hAoise’ or ‘The Spirit of the Age’ decreed that these Nemetons” were always situated close to the sea, to lakes or to rivers, so that the effervescence of the waters, ‘the bubbles of Imbas’, in other words ‘the bubbles of full knowledge’ could be accessed and utilised to the full.

It is true to say then that a modern Nemeton could be described as a spiritual place and inspirational space. A twenty-first century sanctuary, close to all the cultural concepts of our technological world, yet all the while reaching back to our rich inherited past, touching and complimenting the ancient objectives of Anamúlacht or ‘Spiritedness’ which a Neimheadh/Nemeton originally stood for.

View these photos in a gallery